The Cardinal

Brief Synopsis

Cast & Crew

Otto Preminger

Tom Tryon

Carol Lynley

Dorothy Gish

Maggie Mcnamara

Bill Hayes

Film Details

Technical Specs

Synopsis

In 1917 young Stephen Fermoyle returns to his native Boston as a newly ordained Roman Catholic priest. Upon learning that their daughter, Mona, is planning to marry a Jewish boy, the strong-willed Fermoyle family is so openly rude that the lad changes his mind. Consequently, Mona runs away and becomes the partner of a tango dancer. Stephen's arrogant nature causes the crusty but humane Archbishop Glennon to send him to a remote country parish, and there he learns his first lesson in humility from the dying Father Halley. He discovers that Mona is about to have an illegitimate child and that her life can be saved only if the infant's cranium is crushed. All too aware of Catholic dogma, Stephen denies permission and Mona dies. Haunted by the incident, he takes a year's leave of absence from his position with the Vatican diplomatic corps and becomes a teacher in Vienna. After a romantic but unfulfilled encounter with Anna, one of his students, he decides that the Church is his true vocation. Upon his return to Rome, he irritates most of his superiors by defending the rights of a black priest to have a parish in Georgia. As a result of his courageous fight against the Ku Klux Klan, he is promoted to Bishop. Just prior to World War II, he is sent to Austria in an unsuccessful attempt to persuade Cardinal Innitzer to oppose the Nazis. Subsequently, the two have a narrow escape when the Nazis attack the Austrian diocese. As the war begins, Fermoyle is appointed Cardinal, and his proud family travels from America to watch their son assume the robes of his office.

Director

Otto Preminger

Cast

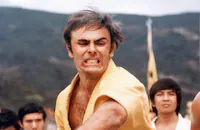

Tom Tryon

Carol Lynley

Dorothy Gish

Maggie Mcnamara

Bill Hayes

Cameron Prud'homme

Cecil Kellaway

Loring Smith

John Saxon

James Hickman

Bernice Gahm

John Huston

José Duval

Peter Maclean

Robert Morse

Billy Reed

Pat Henning

Burgess Meredith

Jill Haworth

Russ Brown

Raf Vallone

Tullio Carminati

Ossie Davis

Don Francesco, Of Veroli Mancini

Dino Di Luca

Carol Lynley

Donald Hayne

Chill Wills

Arthur Hunnicutt

Doro Merande

Patrick O'neal

Murray Hamilton

Romy Schneider

Peter Weck

Rudolf Forster

Josef Meinrad

Dagmar Schmedes

Eric Frey

Josef Krastel

Mathias Fuchs

Vilma Degischer

Wolfgang Preiss

Jurgen Wilke

Eric Van Nuys

Stephen Skodler

Crew

Jack Atcheler

Bill Barnes

Saul Bass

Leon Birnbaum

Fred Bockstahler

Donald Brooks

Hope Bryce

Abbot At Casamari Don Nivardo Buttarazzi

Gene Callahan

Monks Of The Abbey At Casamari

Bryan Coates

Art Cole

Robert Dozier

Kathleen Fagan

Morris Feingold

Robert Fiz

Tom Frewer

Walter Goss

Fred Hall

Donald Hayne

Robert Jiras

Frederic Jones

Joe King

Red Law

Hermann Leitner

Harold Lewis

Louis R. Loeffler

Guy Luongo

Leo Mccreary

Saul Midwall

Eva Monley

Jerome Moross

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

George Newman

Otto Niedermoser

Gerry O'hara

Paltscho Of Vienna

Piero Portalupi

Otto Preminger

Morris Rosen

Nat Rudich

Rector At Casmari Don Raffaele Scaccia

Martin C. Schute

Buddy Schwab

Leon Shamroy

Max Slater

Dick Smith

Harrison Starr

Al Stillman

Eric Von Stroheim Jr.

Peter Thornton

Flo Transfield

Paul Uhl

Bob Vietro

Paul Waldherr

Henry Weinberger

Lyle Wheeler

Film Details

Technical Specs

Award Nominations

Best Art Direction

Best Cinematography

Best Costume Design

Best Director

Best Editing

Best Supporting Actor

Articles

The Cardinal (1963) - The Cardinal

Preminger's career is often seen as divided roughly between two periods. His early work, mostly under contract to 20th Century-Fox, is marked by a series of moody films noir starting with the classic Laura (1944) and including such minor classics as Fallen Angel (1945) and Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950). After Fox, Preminger moved into independent production on an increasingly large scale. Later films like Exodus (1960) and Advise and Consent (1962) are marked by name-studded casts and extensive location shooting. The Cardinal clearly falls into the latter category, with a cast including rising stars Tom Tryon, Carol Lynley and Romy Schneider alongside seasoned veterans like Cecil Kellaway, John Huston, Raf Vallone, Burgess Meredith and, in her last film, silent screen legend Dorothy Gish. It also was shot largely on location, with cameras capturing the New England locales in Massachusetts and Connecticut, the Casamari Abbey in Veroli, the Stana Maria Sopra Minerva in Rome and St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna. Much of the European footage was shot in 35mm but later blown up to 70mm for the picture's roadshow presentation, an inevitable element of epic filmmaking in the 1960s. Beyond the film's size, The Cardinal also represents Preminger's later period in his almost objective use of the camera. He moves his camera and cuts without overemphasizing story details, leaving viewers to put the pieces together on their own, much as in real life.

The film was adapted from Henry Morton Robinson's 1950 bestseller, rumored to have been inspired by the career of Francis Joseph Cardinal Spellman. It follows the career of Stephen Fermoyle, a young Irish Catholic priest ordained in 1917 Boston. What follows is a series of challenges as he deals with his sister's romance with a Jew, her subsequent illegitimate pregnancy, the decision to let her die so her baby may live, the temptation to give up the priesthood for love, a battle to let a black priest open a church in the South and an attempt to protect the church from the Nazi acquisition of Austria.

Access to the various churches and cathedrals that figure prominently in the plot would require cooperation from the Catholic Church. Given The Cardinal's controversial subject matter - questioning church positions on interfaith marriage and the sanctity of life and at times presenting it as a hide-bound institution in need of reform - that would have seemed problematic. Nor did it help that Cardinal Spellman was vehemently opposed to any film adaptation. He had, in fact, exercised enough pressure to keep Hollywood from adapting Robinson's novel for years.

Preminger, however, was never one to shy away from a fight, suggesting that attacks by the real-life prelate would help the film at the box office. He first signed Robert Dozier to craft the adaptation and spent three months working with him. Still unsatisfied, he enlisted Gore Vidal and Ring Lardner, Jr., both atheists and neither with much regard for the original novel. Feeling that Vidal had contributed the lion's share of the writing, Preminger submitted the credit to the Screen Writers Guild. They ruled, however, that the credit had to include both Dozier and Vidal, listed in alphabetical order. At that point, Vidal withdrew his name from consideration.

As the production date neared, Preminger began experiencing some pushback from Spellman, who used his influence to scare off members of the clergy approached to serve as technical advisors and keep the crew from filming in any Boston churches. The director turned instead to former priest Donald Hayne, who had served as technical advisor on The Ten Commandments (1956). He helped the production connect with a Connecticut bishop who had no problem making St. John's Catholic Church available to him. Things were much smoother in Europe, where Hayne's connections helped win permission to shoot at several key locations. The Vatican liaison for the European shoot was Joseph Ratzinger, a young priest who would eventually become Pope Benedict XVI.

For the leading role, which dominates the action, Preminger decided not to go with an established name. Instead, he set out to make Tom Tryon a star. Tryon had been an actor for over a decade, with mostly television credits to his name. He was probably best known for playing Texas John Slaughter, a real life Western hero, in 17 episodes of Walt Disney's The Wonderful World of Color. During the screen test, director and actor got along fine, and he ended up doing a better test than two other young actors, Robert Redford and Warren Beatty. When people warned Tryon about working with Preminger, he countered that the director had been kind and helpful during the test. "I have a rapport with Otto and we're going to get on just fine," he claimed. (Tom Tryon, quoted in Foster Hirsch, Otto Preminger: The Man who Would Be King). That rapport would not survive the first day of shooting.

For the role of Tryon's mentor, savvy Boston Cardinal Glennon, Preminger tried to cast Orson Welles, who claimed he didn't understand the character. Then the director's brother, Ingo, suggested another legendary film director, John Huston. It took some persuading. Huston had not done any significant acting since his early stage work in the 1920s. He had appeared in some of his own and his father's films, but only in cameo roles like the tourist who gives Humphrey Bogart a handout in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). A fan of Preminger's work and his politics, particularly his reputation for challenging the censors and his hiring blacklisted writers, Huston agreed to play the part in return for two paintings by Irish artist Jack Yeats. He ended up stealing the film and getting good reviews even from critics who panned the picture. He also received the Golden Globe and an Oscar® nomination for Best Supporting Actor. The film started him on a second career as a character actor, which proved an easy way to pick up extra money when he was trying to finance a new project or had overindulged at the gambling tables.

One area on which Huston and Preminger disagreed was the treatment of Tryon, whom the director browbeat mercilessly. The first day of shooting was at the church in Stamford, near Tryon's hometown of Hartford, and the actor's parents and friends traveled to the set to watch him start on what everybody expected to be a star-making role. When 69-year-old character actor Cecil Kellaway kept blowing his lines, Preminger took out his frustration on Tryon and fired him in front of cast, crew, friends and family. As the actor started changing into his own clothes to leave, Preminger called him back to the set to finish the shot, treating the whole incident as some kind of practical joke. After observing behavior like that, Huston advised Preminger to handle the actor gently if he wanted to get a good performance out of him, but the director's version of that was to walk up behind the actor before one scene started and scream "Relax!," which tended to have the opposite effect. Preminger's treatment on this and the later In Harm's Way (1965) was one factor that led to Tryon's giving up acting to turn to writing, a career in which he proved much more successful. In later years, Preminger used to joke that Tryon should thank him for pushing him out of out of acting so he could find his true calling as a writer.

Preminger's temper found other victims, too. Cameron Prud'Homme, cast as Tryon's father, was so terrorized by him he could barely get his lines out. Carroll O'Connor was called in during post-production to dub them. The only actors he didn't try to browbeat were veterans Huston and Raf Vallone and Carol Lynley, because he knew they would have given it right back to him. He also was extremely solicitous of Maggie McNamara, an actress who had fallen on hard times after making her film debut in his The Moon Is Blue (1953).

Despite Cardinal Spellman's efforts, The Cardinal was warmly received by the church, with Cardinal Cushing praising it publicly and the Vatican honoring Preminger with the Grand Cross of Merit. Reviews, however, were decidedly mixed. Although the film was welcomed by the New York Post, whose Irene Thirer called it "pictorially exquisite, intelligently cast, and painstakingly, if not thrillingly directed," other critics were harsher. Judith Crist of the New York Herald Tribune dubbed it "a mélange of meandering melodrama, mouthed pieties, and pretentious irrelevance."

Still, the film performed well at the box office, which was reflected in the more commercial end-of-year awards. In addition to Huston's award, the film picked up the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture, Drama. The Academy® nominated it for Best Director, Best Supporting Actor, Cinematography, Art Direction, Costumes and Editing. In later years, the film, though not ranked among his best works, has been given a more positive evaluation by critics on the strength of the director's objective camera work, subtle approach to the leading character's emerging spirituality and treatment of controversial issues.

Producer-Director: Otto Preminger

Screenplay: Robert Dozier, based on the novel by Henry Morton Robinson

Cinematography: Leon Shamroy

Music: Jerome Moross

Cast: Tom Tryon (Stephen Fermoyle), Carol Lynley (Mona Fermoyle/Regina Fermoyle), Dorothy Gish (Celia), Maggie McNamara (Florrie), Bill Hayes (Frank), Cameron Prud'Homme (Din), Cecil Kellaway (Monsignor Monaghan), John Saxon (Benny Rampell), John Huston (Glennon), Robert Morse (Bobby), Pat Henning (Hercule Menton), Burgess Meredith (Father Ned Halley), Jill Haworth (Lalage Menton), Raf Vallone (Cardinal Quarenghi), Tullio Carminati (Cardinal Giacobbi), Ossie Davis (Father Gillis), Chill Wills (Monsignor Whittle), Arthur Hunnicutt (Sheriff Dubrow), Doro Merande (Woman Picket), Patrick O'Neal (Cecil Turner), Romy Schneider (Annemarie), Wolfgang Preiss (S.S. Major), Glenn Strange (Redneck).

C-176m.

by Frank Miller

The Cardinal (1963) - The Cardinal

Ossie Davis (1917-2005)

He was born Raiford Chatman Davis on December 18, 1917 in Cogdell, Georgia. His parents called him "R.C." When his mother registered his birth, the county clerk misunderstood her and thought she said "Ossie" instead of "R.C.," and the name stuck. He graduated high school in 1936 and was offered two scholarships: one to Savannah State College in Georgia and the other to the famed Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, but he could not afford the tuition and turned them down. He eventually saved enough money to hitchhike to Washington, D.C., where he lived with relatives while attending Howard University and studied drama.

As much as he enjoyed studying dramatics, Davis had a hunger to practice the trade professionally and in 1939, he left Howard University and headed to Harlem to work in the Rose McClendon Players, a highly respected, all-black theater ensemble in its day.

Davis' good looks and deep voice were impressive from the beginning, and he quickly joined the company and remained for three years. With the onset of World War II, Davis spent nearly four years in service, mainly as a surgical technician in an all-black Army hospital in Liberia, serving both wounded troops and local inhabitants before being transferred to Special Services to write and produce stage shows for the troops.

Back in New York in 1946, Davis debuted on Broadway in Jeb, a play about a returning black soldier who runs afoul of the Ku Klux Klan in the deep south. His co-star was Ruby Dee, an attractive leading lady who was one of the leading lights of black theater and film. Their initial romance soon developed into a lasting bond, and the two were married on December 9, 1948.

With Hollywood making much more socially conscious, adult films, particularly those that tackled themes of race (Lonely Are The Brave, Pinky, Lost Boundaries all 1949), it wasn't long before Hollywood came calling for Davis. His first film, with which he co-starred with his wife Dee, was a tense Joseph L. Mankiewicz's prison drama with strong racial overtones No Way Out (1950). He followed that up with a role as a cab driver in Henry Hathaway's Fourteen Hours (1951). Yet for the most part, Davis and Dee were primarily stage actors, and made few film appearances throughout the decade.

However, in should be noted that much of Davis time in the '50s was spent in social causes. Among them, a vocal protest against the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, and an alignment with singer and black activist Paul Robeson. Davis remained loyal to Robeson even after he was denounced by other black political, sports and show business figures for his openly communist and pro-Soviet sympathies. Such affiliation led them to suspicions in the anti-Communist witch hunts of the early '50s, but Davis, nor his wife Dee, were never openly accused of any wrongdoing.

If there was ever a decade that Ossie Davis was destined for greatness, it was undoubtly the '60s. He began with a hit Broadway show, A Raisin in the Sun in 1960, and followed that up a year later with his debut as a playwright - the satire, Purlie Victorious. In it, Davis starred as Purlie, a roustabout preacher who returns to southern Georgia with a plan to buy his former master's plantation barn and turn it into a racially integrated church.

Although not an initial success, the play would be adapted into a Tony-award winning musical, Purlie years later. Yet just as important as his stage success, was the fact that Davis' film roles became much more rich and varied: a liberal priest in John Huston's The Cardinal (1963); an unflinching tough performance as a black soldier who won't break against a sadistic sergeant's racial taunts in Sidney Lumet's searing war drama The Hill (1965); and a shrewd, evil butler who turns the tables on his employer in Rod Serling's Night Gallery (1969).

In 1970, he tried his hand at film directing, and scored a hit with Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970), a sharp urban action comedy with Godfrey Cambridge and Raymond St. Jacques as two black cops trying to stop a con artist from stealing Harlem's poor. It's generally considered the first major crossover film for the black market that was a hit with white audiences. Elsewhere, he found roles in some popular television mini-series such as King, and Roots: The Next Generation (both 1978), but for the most part, was committed to the theater.

Happily, along came Spike Lee, who revived his film career when he cast him in School Daze (1988). Davis followed that up with two more Lee films: Do the Right Thing (1989), and Jungle Fever (1991), which also co-starred his wife Dee. From there, Davis found himself in demand for senior character parts in many films throughtout the '90s: Grumpy Old Men (1993), The Client (1994), I'm Not Rappaport (1996), and HBO's remake of 12 Angry Men (1997).

Davis and Dee celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 1998 with the publication of a dual autobiography, In This Life Together, and in 2004, they were among the artists selected to receive the Kennedy Center Honors. Davis had been in Miami filming an independent movie called Retirement with co-stars George Segal, Rip Torn and Peter Falk.

In addition to his widow Dee, Davis is survived by three children, Nora Day, Hasna Muhammad and Guy Davis; and seven grandchildren.

by Michael T. Toole

Ossie Davis (1917-2005)

Quotes

Trivia

Notes

Location scenes filmed in Boston, Stamford, Connecticut, Rome, Vienna, and Stowe, Vermont. Filmed in 35mm and blown up to 70mm for some roadshow presentations.

Miscellaneous Notes

Voted One of the Year's Ten Best Films by the 1963 National Board of Review.

Released in United States on Video July 13, 1994

Released in United States Winter December 1963

Released in United States on Video July 13, 1994

Released in United States Winter December 1963