Cold Turkey

Brief Synopsis

Cast & Crew

Norman Lear

Dick Van Dyke

Pippa Scott

Tom Poston

Edward Everett Horton

Bob Elliott

Film Details

Technical Specs

Synopsis

Public relations director Merwin Wren, inspired by the irony that the Nobel Peace Prize's founder made his fortune manufacturing explosives used in rifles, schemes to promote the elderly owner of Valiant Tobacco Company, Hiram C. Grayson, as a great humanitarian in the tradition of Alfred Nobel. To accomplish this, Wren convinces the company's board of directors to offer $25,000,000 to any town that can stop smoking "cold turkey" for thirty days, certain that none will ever claim the prize. In Eagle Rock, Iowa, where the closing of an airbase has caused economic depression, Rev. Clayton Brooks hopes his church will re-assign him to the wealthy community of Dearborn, Michigan. The vainly handsome Brooks is popular with everyone except his meek wife Natalie, who stoically submits to his constant criticism and his accusations that she subconsciously sabotages his ambitions. Brooks preaches to his congregation that God has plans for their town and when he learns about the prize, decides that Valiant's offer is the "purpose" God intended for them. With the approval of the town council, the dynamic preacher leads a campaign to persuade the townspeople to pledge to quit smoking for one month. After ninety-eight percent of the population signs the pledge, Valiant's directors get uneasy, but Wren assures them that people cannot possibly remain smoke-free for long. In Eagle Rock, of the remaining two percent of holdouts, the most challenging is Edgar Stopworth, a wealthy alcoholic, whom Brooks, a former college boxing champion, bullies into leaving town for the month. The chain smoking Dr. Proctor is coerced into giving up his three packs a day habit when the local banker threatens to foreclose on the doctor's hospital unless he signs the pledge. Six hours before the deadline for signing the pledge, thirty members of the anti-Communist "Christopher Mott Society" led by Amos Bush have stubbornly refused to sign up, although none of them smoke. To obtain their cooperation, they are appointed the task of policing and reporting violations, and are promised yellow and red caps and armbands. When the town clock strikes midnight, smokers take their last puffs and Stopworth drives away, while the Motts set up blockades at town boundaries to search incoming cars for tobacco products. Each person suffers withdrawal in his own way, by becoming short-tempered, overeating or biting nails, and neighbors rush to intervene whenever the weak-willed threaten to give up. Intrigued by the events, newcomers move in, among them, a prostitute masseuse and a pseudo-Buddhist. Wren drives into Eagle Rock with a carload of cigarettes, but is stopped at the blockade by addled octogenarian Mott member Odie Perman, who thinks he is a Communist and holds him at gunpoint. By the eleventh day, Eagle Rock has the nation's sympathy and a radio program doctor suggests that married couples participate in the "act of physical love" as a substitute for smoking. Hearing this, Brooks reaches for Natalie, who resigns herself to his increasingly frequent attention toward her. After the directors point out that there is no safeguard to determine if anyone cheats, members of the "Sons of the Confederacy," a pseudo-military group, are sent to watch out for Valiant's interests. As tension increases, Wren roams the streets with his cigarette lighter, which is shaped like a gun, in search of people with a cigarette needing a light. Relieved to see townspeople become increasingly miserable and even violent, Wren reports hopefully to the board that the town's failure is imminent. During a council meeting in which officials argue over how to spend the prize money, Brooks receives an emergency summons to the hospital's operating room. Rushed there by police car, and followed by the whole council, Brooks finds Proctor trying to light up, insisting that he needs a cigarette before undertaking an operation. After slugging the nurse and threatening the others with his scalpel, Proctor has everyone at a standoff, when doors open and the beloved newscaster Walter Chronic enters the room and everyone stops what they are doing. To exploit the many tourists arriving daily, the citizens turn their houses into museums and set up food and souvenir stands selling "Cold Turkey" dolls that say, "I love you" and "Smoking gives you cancer," and masks featuring the faces of town officials. Nationally known companies pay large sums to put up billboards, and a movie maker proposes to film in Eagle Rock. On the pretense of wanting to "help," Col. Glen Galloway, a Pentagon liaison, arrives to find a way for the president to share the good publicity. Noting how Eagle Rock commands media attention and public sympathy, Valiant and the rest of the tobacco industry fears for its future. At the town square in the midst of the hubbub, Brooks sees Eagle Rock's young people protesting that their elders should "make sense, not money," and wonders if their generation has lost their sense of civic duty. When Brooks agrees to let a television crew into his church, his sermon is interrupted by the television director, who gives him stage directions. Later, disturbed by the town's carnival atmosphere, Brooks has doubts about what he has created. When his supervisor Bishop Cross visits, Brooks apologizes for the town's greed and avarice, but the bishop praises its "vitality" and "unity of purpose." Referring to the latest edition of Time magazine featuring Brooks on the cover, Cross says that in the "God business" nothing is bigger and predicts that Brooks will be assigned to the Dearborn church. That evening, Natalie suggests that Eagle Rock is "gaining the world, but losing its soul." Offended that she quoted scripture, Brooks accuses her of turning his "very own words" against him. Citing Time as proof, he brags that he is now in league with the Pope, Winston Churchill, Jonas Salk and the president, all of whom have appeared on the magazine's cover. Chagrinned, Natalie fantasizes about screaming from her rooftop. On the last day of the month, the major television networks prepare to broadcast the presentation of the prize check, as the Sons of the Confederacy continue to watch for smokers. Galloway offers to fly the council to Washington, D.C. for the ceremony so that they can be filmed with the president on a split-screen, but he is ignored. At eleven p.m., as the town gathers at the bandstand and Valiant's board members wait unhappily in a limousine to present the check, a man hired by Wren moves the town clock's hands forward while Wren pushes through the crowd with his gun-shaped lighter. When the clock strikes midnight ten minutes early, cigarettes drop from a helicopter into the crowd. Brooks persuades the people to wait before lighting up, but Proctor goes missing and Brooks orders the crowd to find and stop him from smoking. Wren searches for Proctor, too, but accidentally drops his lighter just as Odie spots him. Calling Wren a Communist, she points her gun at him, which he mistakes for his lighter. He grabs it and, while trying to light Proctor's cigarette with it, shoots Proctor. To honor Proctor's "last request" for a cigarette, Wren pleads with the crowd for a lighter. Stopworth, who has just returned and who also owns a gun-shaped lighter, finds Odie's gun and, making the same mistake as Wren, unintentionally shoots the ad man with it. Odie, who is still chasing Communists, grabs the gun and aims at Wren, but shoots Brooks instead. At midnight, everyone's attention is focussed on the chance to smoke, and consequently the dying men sprawled on the road behind them go unnoticed. After a motorcade arrives with the president, a Goodyear blimp floating above the crowd announces that Eagle Rock is to be the site of a new missile plant. Sometime later, four towers of the factory spew black smoke into the air above Eagle Rock.

Director

Norman Lear

Cast

Dick Van Dyke

Pippa Scott

Tom Poston

Edward Everett Horton

Bob Elliott

Ray Goulding

Vincent Gardenia

Barnard Hughes

Graham Jarvis

Jean Stapleton

Barbara Cason

Judith Lowry

Sudie Bond

Helen Page Camp

Paul Benedict

Simon Scott

Raymond Kark

Peggy Rea

Woodrow Parfrey

George Mann

Charles Pinney

M. Emmet Walsh

Gloria Leroy

Eric Boles

Jack Grimes

Walter Sande

Harvey Jason

Bob Newhart

Louis Zorich

Glenn Yarbrough

Ted Knight

Charles White

Robert Christopher

Burt Prelutsky

Mrs. Burt Prelutsky

Crew

Arch Bacom

Jerry Best

Claude Binyon Jr.

Ross Brown

Brian Brunette

William Croft

Marion Dougherty

Robert Downey

William Price Fox Jr.

Dick Glazer

Ralph Hall

C. Mason Harvey

Paul Hochman

John C. Horger

Mary Keats

Norman Lear

Norman Lear

Norman Lear

Arthur Morton

Randy Newman

Randy Newman

Phill Norman

Clark Paylow

Fred Price

Art Pullen

William Randall

Margaret Rau

Neil Rau

Rita Riggs

John P. Riordan

Aaron Rochin

Sid Sidney

Mac St. Johns

Edward S. Stephenson

Jane Thompson

Duane Toler

Tom Tuttle

Dick Van Dyke

Tony Wade

Herb Wallenstein

Isaac Watts

Charles F. Wheeler

Jack Whitman

Bud Yorkin

Film Details

Technical Specs

Articles

Cold Turkey

In a pre-credits sequence, Merwin Wren (Bob Newhart), the public relations man for the Valiant Tobacco Company, has his wheelchair-bound boss, Hiram Grayson (Edward Everett Horton), right where he wants him. Wren tells Grayson that he has a terrific idea, "The Capper" of his twenty years in public relations: just as munitions manufacturer Alfred Nobel spent a fraction of his fortune to create The Nobel Prize, Grayson should offer a prize of $25 Million to any town whose residents can quit smoking for thirty days straight. The publicity will be enormous, Grayson's name would be associated with Good Works, and, as Wren reassures a nervous board of directors, "You're overlooking one thing - have you ever seen a whole office building give up smoking? A whole neighborhood?" Confident that there is no way an entire community can successfully stop the habit as a group, the board votes to go ahead with the offer.

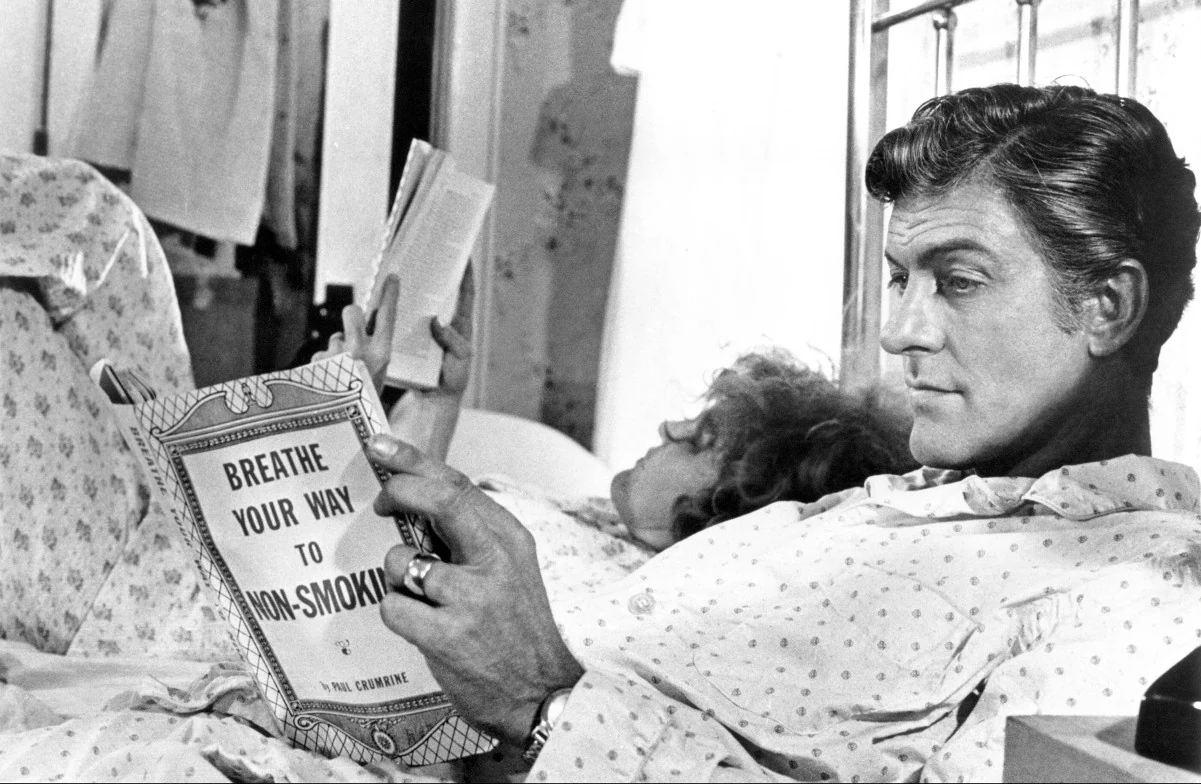

The Valiant board did not count on Eagle Rock, Iowa - population 4,006. During the opening credits, we see a black mutt wandering into town, past dilapidated business signs marked "Closed" and "Moved." The depressed state of the city is further emphasized by the forlorn Randy Newman song, "He Gives Us All His Love." The churches are about the only establishments in town in full vigor, and we meet the Reverend Clayton Brooks (Dick Van Dyke) trying to stir up his sleepy, dull-witted parishioners. When the ambitious Brooks hears about the Valiant offer, he persuades the town council and the citizens to take the challenge. What follows is a series of vignettes in which the diehards are dealt with (Tom Poston is superb as a wealthy alcoholic who does not want to play along), the anti-Communist "Christopher Mott Society" (a parody of the John Birch Society) refuses to sign up, and the many consequences of "withdrawal syndrome" are faced.

In addition to finely-etched characterizations from such wonderful comic actors as Vincent Gardenia, Barnard Hughes, Jean Stapleton, and Paul Benedict, radio comics Bob (Elliot) and Ray (Goulding) appear as multiple characters. Bob and Ray are most welcome, in fact; they are instrumental in softening some of the mean-spirited humor and upping the satirical quotient as they portray high-profile news correspondents who descend upon the town. Their thinly-disguised personas include "David Chetley," "Hugh Upson," and "Walter Chronic."

Lear's screenplay was based on an unpublished novel by Margaret and Neil Rau called I'm Giving Them Up for Good. Cold Turkey was shot entirely on location in Iowa, not in the fictional town of Eagle Rock, but in Winterset, Greenfield and Des Moines. Cinematographer Charles F. Wheeler takes advantage of the natural setting and many scenes, such as one depicting Rev. Brooks' morning jog, are bathed in gorgeous Midwestern light. Apparently production wrapped in 1969 and the film sat on the shelf unreleased for nearly two years. Consequently it is a posthumous credit and the last film appearance for Edward Everett Horton, who died in 1970.

Critical reaction to Cold Turkey was mixed; that is to say, most critics seemed to simultaneously dislike the vulgar humor while still admitting the film was funny. Vincent Canby, for example, writing in the New York Times, called Cold Turkey a "very engaging, very funny movie," but admitted that it contained "...a lot of typical, nasty humor and old-fashioned, clean-cut vulgarity." Canby noted, "there are moments when the movie makes a few, half-hearted attempts to say something about the evils of greed and avarice, but its concerns are both more immediate (to get laughs out of things like false teeth and flatulence) and its intentions more specific (to question the economic system that must punish as it rewards)." Finally, Canby said that the film "...is not terribly significant satire. It was made - after all - to amuse the very people it is satirizing, but it does this with such hustling, commercial vitality that I found most of it irresistible..." Similarly, Roger Ebert wrote that the movie "...assume[s] as a matter of course that the human being is powered with unworthy motives, especially greed," and that it was a movie "...that I can recommend to cynics and malcontents with little fear they'll be disappointed." At the same time, Ebert wrote, "...Lear makes it work by a brilliant masterstroke: He gets the comedy, not out of people trying to stop smoking, but out of the people themselves ...during a series of vignettes handled by Lear with an unfailing eye for human frailty. Even if you don't smoke, you'll find Cold Turkey funny."

In a long piece written for New York Magazine, Judith Crist noted that at least Cold Turkey was made for and about adults, and was breaking what she felt was a long line of "youth oriented" films that had been flooding screens since The Graduate (1967) and Easy Rider (1969), so "...we're free of Beautiful Youth vs. Rotten Society. With Cold Turkey it's a case of Norman Lear vs. Rotten Society." Crist goes on: "One tends to be grateful for small favors these days - And getting Bob and Ray pure in their impersonations of major newscasters, Bob Newhart in his buttoned-down-mind routine as a p.r. man who tells it 'from le coeut,' or the late Edward Everett Horton as a prune-like tycoon aglow with venality is among the pleasures on hand." But above all, Crist writes, "...Lear is merciless in his consideration of the common man, whom he obviously sees as the alum rather than salt of the earth....There is a touch of black to Lear's comedy, one that does not blend easily with the too much that is bland. Lear tends to linger long on the obvious; indeed, high spots of the film are provided by flashes of slapstick withdrawal-symptom scenes, provided by Robert Downey as a second-unit director."

Cold Turkey marked the first film score written by Randy Newman, the nephew of famed composer Alfred Newman. Kevin Courrier, biographer of the younger Newman, wrote (in Randy Newman's American Dreams, Ecw Press, 2005) that the film's music "...was a droll blend of [Aaron] Copland and his Uncle Alfred, but he dismissed the effort later, saying it wasn't a real score because he merely sketched it out and left the rest to Jerry Goldsmith's regular orchestrator, Arthur Morton." Courrier also quoted Newman, who said, "It's always scared me to write for orchestra. With experience, I've gotten better about it. This job, being the first, really got to me." The movie's featured song, "He Gives Us All His Love," made its debut here before appearing on Newman's classic 1972 album Sail Away.

Producer: Norman Lear

Director: Norman Lear

Screenplay: Norman Lear (screenplay); Norman Lear, William Price Fox, Jr. (screen story); Margaret Rau, Neil Rau (novel)

Cinematography: Charles F. Wheeler

Art Direction: Arch Bacon

Music: Randy Newman

Film Editing: John C. Horger

Cast: Dick Van Dyke (Rev. Clayton Brooks), Pippa Scott (Natalie Brooks), Tom Poston (Mr. Stopworth), Edward Everett Horton (Hiram C. Grayson), Bob (Hugh Upson/David Chetley/Sandy Van Andy), Ray (Walter Chronic/Paul Hardly/Arthur Lordly), Vincent Gardenia (Mayor Wappler), Barnard Hughes (Dr. Proctor), Graham Jarvis (Amos Bush), Jean Stapleton (Mrs. Wappler)

C-100m. Letterboxed.

by John M. Miller

Cold Turkey

Quotes

Big clocks are never wrong!- Wren

Trivia

The bulk of the film was shot in Greenfield, Iowa, with many of the actual residents playing extras in many scenes.

Notes

Opening credits appear after two sequences in which the character "Merwin Wren" explains his idea to "Hiram C. Grayson," then convinces the Valiant's board to implement the scheme. During the opening credits, under which Randy Newman's song "He Gives Us All His Love" is heard, a dog wanders to Eagle Rock on a road lined with billboards advertising the town's establishments that have since moved or gone out of business. As indicated by the signs, only the churches are still active. The dog reappears near the end of the film, when it runs past the dying men, while the Newman's song is reprised on the soundtrack. Dick Van Dyke's opening onscreen credit reads: "Rev. Clayton Brooks as played by Dick Van Dyke." A cast list appears only in the opening credits, and most of the crew members are listed in the ending credits.

According to the Variety and Daily Variety reviews, the film was based on an unpublished novel by the husband and wife team, Margaret and Neil Rau. Information found in the file for the film at the AMPAS Library indicated that the title of the unpublished work was I'm Giving Them Up for Good. Although a December 1967 Hollywood Reporter news item reported that Vernon Zimmerman was signed to collaborate on the script, he was not listed in the onscreen credits and his contribution to the final film has not been determined. The title Cold Turkey was taken from a slang term that refers to an abrupt and complete withdrawal from an addictive substance.

A studio cast list contained in the file for the film in the AMPAS library erroneously credits actor Stanley Gottlieb with the role of "Hiram C. Grayson" and lists Charles Pinney, who portrayed "Col. Glen Galloway," as Jack Pinney. Bob Elliott and Ray Goulding's opening onscreen credit reads "Bob and Ray," which was the name of their comedy act. The team marked their feature film debut in Cold Turkey impersonating several contemporary television news reporters, using slightly altered names. In his portrayal of "Walter Chronic," Goulding parodied Walter Cronkite, the highly respected newsman who anchored The CBS Evening News from 1961 until his retirement in 1981. The character "David Chetley," portrayed by Elliott, was a parody of the news team David Brinkley and Chet Huntley of the The Huntley-Brinkley Report, which aired on NBC from 1956 until 1970. During the film, both Bob and Ray are sometimes depicted with "haloes" created by positioning the actors under a round florescent light or surrounded by rays from the sunlight.

The John Birch Society, depicted in the film as the "Christopher Mott Society" and the Sons of Confederate Veterans were other real-life institutions that were parodied. Several contemporary personalities, among them, President Richard M. Nixon, appear in stock news footage. Nixon is also portrayed by an actor whose face is never shown, but who is seen from the back extending his arms in the characteristic gesture that was associated with Nixon.

According to June 1969 Hollywood Reporter and Daily Variety news items, the film was shot on location in Winterset, Greenfield and Des Moines, IA, and many Iowan citizens were cast as extras. The film ends with the acknowledgment: "With love and thanks to the Good People of Iowa," a reference to which the LAHExam and San Francisco Chronicle reviewers took exception. The San Francisco Chronicle reviewer felt that the film "cruelly" satirized the Iowan citizens.

Tandem Productions was owned by Lear and his partner, Bud Yorkin. Although Van Dyke is not personally credited onscreen as producer, his company, DFI Productions (Dramatic Features, Inc.), was a co-producer, as noted by the ending credits, December 1967 Daily Variety and March 1967 LAHExam news items, and the Daily Variety review. Modern sources add to the cast Maureen McCormick (Voice of doll) and Lynn Guthrie, who is also credited by modern sources as a 2d asst dir. Cold Turkey marked the feature film directorial debut for writer-producer Lear and marked the final film of Edward Everett Horton (1886-1970), who portrayed "Hiram C. Grayson," a character without dialogue.

Miscellaneous Notes

Released in United States Winter January 1, 1971

Released in United States Winter January 1, 1971