Marie: A True Story

Brief Synopsis

Cast & Crew

Roger Donaldson

Sissy Spacek

Jeff Daniels

Keith Szarabajka

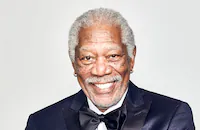

Morgan Freeman

Don Hood

Film Details

Technical Specs

Synopsis

Tennessee housewife Marie Ragghianti has a child with serious health problems and is married to an abusive husband. Resolute about improving her life, Marie leaves her husband and returns to school, eventually getting her college degree and getting a job with the Tennessee State Government. After years of hard work, she becomes the head of the state's parole board. In her new position she becomes aware of corruption that reaches to the highest offices, including the governor. Determined to clean up her department, Marie starts to week out the graft she has discovered, only to be discredited in the press by some of the governor's powerful friends.

Director

Roger Donaldson

Cast

Sissy Spacek

Jeff Daniels

Keith Szarabajka

Morgan Freeman

Don Hood

John Cullum

Sarah Hunley

Dwight Lewis

John-michael Maas

R Pickett Bugg

Fia Porter

Clarence Felder

Vincent Irizarry

Jeff Marcum

Collin Wilcox Paxton

Jerry Rushing

Dawn Carmen

Ivan Green

Bill Mcintyre

J Michael Hunter

Chip Arnold

Fred Thompson

Graham Beckel

Charles Kahlenberg

Robert Green Benson

Macon Mccalman

George Gray

Jane Powell

Larry Brinton

Ruby L Wilson

Michael P Moran

Drue Smith

Phil Markert

Alan Sader

Mac Pirkle

Edward C Carr

Herb Harton

James D. Fields

Lisa Banes

Carla Cantrelle

Trey Wilson

Leon Rippy

Lisa Foster

Joe Sun

David Eddings

Tom Story

Timothy Carhart

Lorenzo Allen

Shane Wexel

Stephen Mckinley Henderson

Crew

Benny Andersson

Carmen Baker

Rick Barefoot

Donah Bassett

Peter Bloor

John Briley

Allan Bromberg

Frank Capra Jr.

Jonathan Capra

Paul Carden

Dan Chichester

Johnny Christopher

Tim Craig

Chrissie Davis

Massimo De'rossi

Karen Everly

Gwyneth Eyers

Mark Fincannon

Ronald Kent Foreman

Neal Mills Forney

Chip Fowler

Kathryn Freeman

Jai Galati

Dan Garde

Jeremy Gee

Jeffrey Ginn

Jeff Goodwyn

Vickie Graef

Doris Grau

John Hernandez

David Hildyard

Bob Howard

Jeff Howery

William Hoy

Mark James

Beth Jones

Jeff Kluttz

David Knight

Eddie Knight

Francis Lai

Tony Lawson

Brenda Lee

Julius Leflore

Jerry Leiber

John Lennon

Tantar Leviseur

Lyn Lucibello

Peter Maas

John Mahaffie

Ronald Mapson

Gilbert Marouani

Paul Mccartney

William Mccaughey

Chris Menges

Chris Menges

Ray O'reilly

Frank O'shea

Michele Panelli-venetis

David Pearson

Bob Penn

Toby F Phillips

Ricky Ragghianti

Jack Riel

Michael Roberts

Aaron Rochin

Roland Romanelli

Arden Sampson

Elliot Schick

Jeffrey Schlatter

Richard Schmitt

Rod Schumacher

Roy Smith

Ken Sprunt

Mike Stoller

Michael Stroud

John Stuart

Tom Taylor

Fred Thompson

Wayne Thompson

Beverly Tomlinson

Joe I Tompkins

Neil Travis

Bj÷rn Ulvaeus

Melissa Walden

Shalina Waran

Don Warner

Robert Waxman

Mentor R Williams

David Wirth

Pamela J Wise

Don Zearfoss

Videos

Movie Clip

Trailer

Hosted Intro

Film Details

Technical Specs

Articles

Taking a Stand (FILM COMMENT) - Taking a Stand - Films air on 5/12

When Sissy Spacek starred in the title role of Roger Donaldson's Marie, in 1985, Roger Ebert shrewdly pegged it as another entry in a new genre about the "young woman with pluck, who struggles against the system and makes a stand for what she believes in." He listed, as examples, Sally Field in Norma Rae (1979) and Places in the Heart (1984), Jessica Lange in Country (1984) and Spacek herself in (among others) Coal Miner's Daughter (1980) and The River (1984).

Three years later, cinematographer Chris Menges, who shot Marie, made his directorial debut in A World Apart, a Cannes Grand Prix winner starring Barbara Hershey as a formidable South African anti-apartheid activist who forfeits domestic happiness for her righteous cause. The genre reached its populist apotheosis 15 years later, with Julia Roberts as brassy, self-made environmental crusader Erin Brockovich (2000). Spacek, though, always said that what she liked most about her characters was their weaknesses.

Spacek's knack for capturing her heroines' soft spots turns Marie, the saga of a whistleblower in the Tennessee state government, into something more affecting than a middle-class Norma Rae. This film isn't just another piece of heroine worship; it's a vivid portrait of a woman backed against the wall, who rises to the best in herself. Smashingly directed by Roger Donaldson (just before his commercial breakthrough in 1987's No Way Out, his brash re-imagining of The Big Clock, 1948), the film tells how Marie Ragghianti, as chairman of Board of Pardons and Paroles in 1977, stood up to political corruption when Governor Ray Blanton's administration started selling clemencies (at scalpers' prices). Marie doesn't simply focus on her courage. It also explores how someone as virtuous as Marie could wait for months before taking decisive action. The movie captures the insidiousness of white-collar crime and dramatizes how those who practice it can be as insulated from their victims as pilots are from bombing targets.

Marie is full of good guys and bad guys, but no one is unblemished. Even Marie's "knight in shining armor," a fellow government worker who finally quits to join her defense, first writes a letter supporting her dismissal. It's a measure of the movie's moral clarity that what counts is not his moment of weakness but his life of truth. Marie herself, a single mother who left a battering husband to work her way through college and ended up with a good-paying state job, is both dedicated and careless. Raising three young children with the marginal help of an invalid mother and taking a job that sends her hurtling all over the state and country, she doesn't make all her meetings or check her expense tabs: she's even late to her first press conference. It's a tribute to Donaldson's direction and Spacek's performance that Marie's loose ends only emphasize her solid core. Spacek clarifies Marie's priorities. Her performance reaches multiple peaks not during professional confrontations, but in the moments when Marie reacts with blazing reflexes to her younger son's repeated bouts of choking. And Donaldson (as he demonstrated in Smash Palace) is such an acute observer of domestic turmoil that the opening tableau of her broken marriage and the ongoing scenes of her Family Circus register as sharply as the violence enacted by the felons whose clemency is auctioned.

When the Blanton administration dismisses Marie, allegedly for taking unearned expenses and overtime but actually for refusing to honor clemencies that have been sold and paid for, she says she's been through worse things in her life. Then and there, Spacek earns our emotional allegiance. She has the confidence to show a public servant's private mettle, and that makes her electric. Marie doesn't start out as a rebel with a cause. She's more like the girl next door, who believes in the people she worked for as a Young Democrat in the heady Watergate era. When she's first brought into the government, she can't help flashing her majorette smile at the governor (Don Hood) and his grinning legal counsel, Eddie Sisk (Jeff Daniels).

The film dramatizes the unspoken sexual suspiciousness that accompanies the Maries of this world into their jobs, and the nonstop flirtation that fosters it, as well as the jockeying for position that results whenever a new head man installs his own people in office. As the evidence of illegalities mounts, Marie must face not only the actively corrupt members of the administration, but also the passively corrupt ones who'll do anything to save their positions. When the snakelike Sisk finds out that Marie has naively reported the clemency irregularities to the governor, Marie accuses her secretary of spying for Sisk. The bureaucratic beast in the paper-pusher comes out. She replies, "My loyalty is to my job."

Donaldson and screenwriter John Briley craft a supple, Reagan-era equivalent to the straightforward Warner Bros. social melodramas of the 1930s. Jeff Daniels uses all the malleability of his long, toothy face to convey the chameleon-like sliminess of a political palm-greaser like Sisk. As Marie's sometimes-erring buddy, Kevin McCormack, one of those nonthreatening good fellows who ends up being a strong woman's best friend (and no more), Keith Szarabajka comes across like a human Kermit. Morgan Freeman brings an elusive and unsettling presence to the role of Parole Board supervisor Charles Traughber, who conveniently fails to remember details about any paid-for clemency. (The movie could use more of Freeman and his character's interactions with Marie.) Trey Wilson, soon to win immortality as the coach in Bull Durham (1988), has a knowing, weathered gruffness as Marie's FBI ally. And as Fred Thompson, the Watergate counsel whom Marie employs to sue Gov. Blanton for unlawful dismissal, the real Fred Thompson, in his acting debut, displays acuity beneath his mulish force. He's like an intellectual Joe Don Baker, walking tall in the courtroom as he sneakily obliterates slick-with-a-drawl John Cullum as the opposing counsel. In addition to its occasional heavy hand, the film has one significant flaw. The climactic trial doesn't seem expansive enough to contain the tapestry of regional decay Donaldson threads off-the-cuff throughout the movie. But the movie as a whole is a hell of a pardoner's tale.

The quicksilver lucidity of Menges's cinematography enables Donaldson, in his American debut, to move swiftly through this film's domestic turmoil, office politics, and thuggery. It was the first feature Menges shot on American soil (after doing inspired work for Ken Loach, Stephen Frears, Neil Jordan, and Roland Joffe). He also brings a fresh, uncondescending eye to locales as unassuming as a roadside gas station/saloon, as august as the Greek Revival-style Tennessee State Capitol, and as forbidding as the Tennessee State Penitentiary (where rioting occurred within a year after production). Menges makes superlative use of the Steadicam to keep up with Marie's perpetual motion, whether she's juggling motherhood and waitressing while studying English and Psychology at Vanderbilt, or entering Nashville's halls of power with the ingratiating, untrustworthy Sisk. Menges doesn't trigger us to ohh and ahh at his virtuosity; he connects us to Marie's nervous system.

As a new director, Menges brings the same lightning responses to the fact-based anti-apartheid drama, A World Apart (1988). The movie fits Ebert's description of his "women with pluck genre" but transcends it, too. As Kevin Courrier wrote on the website Critics at Large, Menges, one of the few world-class cinematographers to do equally distinctive work as a director, always "plays against genre mechanics, frees the material from its more conventional melodramatic underpinnings." In A World Apart he creates an intimate sort of you-are-there realism that sets off tingles of recognition, right from the start. Shawn Slovo, a daughter of Communist anti-apartheid activists Joe Slovo and Ruth First, wrote the autobiographical script rich in remembered detail of South Africa in the early 1960s. Menges brings the screenplay to passionate life. He pulls us into the hush surrounding Diana and Gus Roth (Barbara Hershey and Jeroen Krabbe), parents who are willing to sacrifice their family life--and, maybe, life itself--to the cause. The caution that surrounds Gus going into exile and Diana working for a radical newspaper surrounds their oldest daughter, Molly (Jodhi May) and distances her from her parents.

The movie runs on twin tracks. We follow Molly from dance class to locker room and schoolroom as she strives to achieve a girlish normality despite classmates who label her dad a traitor and her family subversive. And we're swept up in Diana's wake as she argues for the liberation movement of the African National Congress and practices the inclusiveness that she preaches, whether hosting an integrated birthday party or chronicling a work stoppage at a power station.

A World Apartis a triumph of equilibrium. It depicts Molly's anger and heartbreaking yearning for her mother and Diana's heroic strength, especially after she becomes the first woman jailed--and kept in isolation--under the Afrikaner Nationalist regime's 90 Days Detention Act. (She is actually held for 117 days.) Menges and Slovo frame the story so that the family pathos cannot be separated from the tragedy of apartheid. Molly, a bright girl, comprehends the political pressures that envelop her. What defines her, though, is her stubborn honesty, as her personal needs war with her political understanding. She demands an existential closeness to and frankness from her mother that Diana can't provide in this risky, oppressive environment. Molly's adolescent perspective creates an intense texture for a complex socially conscious film. It becomes more affecting as it goes along because Menges and his cinematographer, Peter Biziou, establish the themes intuitively, visually, and immediately, when father and mother steal a final kiss before he departs in the night. Molly must act like a domestic spy in her own house, prowling shuttered or half-lit rooms to arrive at some truth.

Menges modulates the aura of ominousness. Homey nuances become memorable, like the childish food-play among Molly and her two younger sisters at the dinner table, or the conspiratorial expressions flashed by Molly and her best friend Yvonne (Nadine Chalmers) when they're all dressed up at a party. We know these sweet moments of normality can be disturbed at any moment. When Yvonne's ebullient mother June (Kate Fitzpatrick) sees a bike-riding black man struck by a white hit-and-run driver, she yells for the gawking crowd to call a hospital; otherwise, she doesn't want "to get involved." Still, the movie doesn't score cheap points against this conventional woman. June radiates ebullience, something Molly cannot get from Diana. Molly elicits maternal warmth from Elsie, the Roth's housekeeper, played by South African architect-turned-actress Linda Mvusi. To Molly, Elsie exudes the generosity and beauty of an earthy, rooted fairy godmother. She pulls off devastating moments of grief when she learns of a brother's death. Mvusi shared the best female acting prize at Cannes with Hershey and May.

Hershey's performance takes on an awe-inspiring indomitability during Diana's imprisonment. Interrogators work her over not just as a journalist and militant but also as an independent woman. They say they respect women--that's why they're giving her the chance to serve up her co-conspirators and come clean. They attempt to break her down by questioning her virtues as a mother. David Suchet gives a startlingly intelligent, scary performance as her lead questioner. He uses compassion as an investigative tool; his alert eyes make his presence at a Roth jailhouse reunion unbearably invasive. Hershey is never more moving than when she withstands his gaze. Her commitment grows in stature throughout her ordeal until she's willing to make the ultimate self-sacrifice.

Throughout the movie, May is demonstrative enough for them both. She has the keen determination that pegs her as her mother's daughter, but she also has the vulnerability and confusion that Diana has excised from her own personality. May takes us on an emotional whirligig, going hard and soft in flashes. She's stoic when her classmates, including Yvonne, start to shun her at school. But in a burst of neediness she walks to Yvonne's house, only to have the girl's father drag her into his car and drive her home, kicking and screaming.

Everything comes together when Molly's frustrations erupt and she demands that her mother treat her fairly, as if she were grown up. The mother and daughter are finally able to communicate intensely, though we're not sure either of them can change. The climactic scene of them attending Elsie's brother's funeral is equally upsetting and uplifting. Diana risks jail time again, but for once she and Molly unite in loving solidarity.

By the end, the phrase "a world apart" stands not just for the separate worlds of white South Africa, black townships, and persecuted radicals. It ultimately represents the private world of emotion that every person should have the right to keep intact.

by Michael Sragow

To read the article at Film Comment and explore the website, Click Here. To learn more about Film Comment magazine, please visit www.filmcomment.com and to subscribe go to www.filmcomment.com/subscribe-to-film-comment-magazine/.

Taking a Stand (FILM COMMENT) - Taking a Stand - Films air on 5/12

Marie: A True Story -

Filmed on location in Nashville and at the Tennessee State Penitentiary, Marie: A True Story was directed by Roger Donaldson, from a screenplay by John Briley, based on the 1983 book by Peter Maas. Marie Ragghianti (Spacek) leaves her abusive husband in the late 1960s, and goes to school as a single mother with three children. Thanks to a college friend (Jeff Daniels), she gets a job in Governor Ray Blanton's (Don Hood) administration, and works her way up to being the first women to head the Tennessee state parole board. While on the job, she begins to see that the Blanton and his staff are taking bribes from prisoners in exchange for early release. Marie loses her job after she refuses to go along with the corruption, and finds herself up against a very powerful political machine. She fights the good fight, but it comes at a price. Also in the cast were Keith Szarabajka, Morgan Freeman, and John Cullum. Fred Thompson, who had been the attorney for the real Marie, plays himself. It would be his first of many acting roles.

Marie was a role that Spacek couldn't turn down. As she told Bob Thomas, she had first heard the story from her brother, Ed, who was a record promoter in Memphis. When she found out that Maas had written a book about Ragghianti and Dino De Laurentis owned the rights, she felt "desperately" that they needed her. "It's important that I love the project, love the script, that I can relate to the character and yet not completely understand her so that I have to stretch myself. I like films that have a positive effect, an element of hope. When you spend so much time on a film, you have to think positively about it."

Roger Ebert thought positively about Marie: A True Story . In his review for the Chicago Sun-Times , he praised Spacek's performance, not minding that she had played a similar character before, because she played them so well. The film, he wrote, was "absorbing," and his only complaint was "that it's too predictable. There's never really any doubt in our minds that Marie will do the right thing."

By Lorraine LoBianco

SOURCES:

Ebert, Roger "Marie: A True Story" Chicago Sun-Times 18 Oct 85

The Internet Movie Database

Thomas, Bob "Sissy Spacek Couldn't Turn Down Role in 'Marie'" Boca Raton News 13 Oct 85

Thomas, Bob "Sissy Spacek Scores Again in 'Marie: A True Story'" The Fort Scott Tribune 28 Sep 85

Marie: A True Story -

Quotes

Trivia

Miscellaneous Notes

Released in United States Fall October 11, 1985

Began shooting November 1984.

Released in United States Fall October 11, 1985