Bus Stop

Brief Synopsis

Cast & Crew

Joshua Logan

Marilyn Monroe

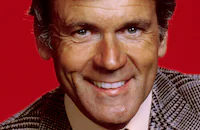

Don Murray

Arthur O'connell

Betty Field

Eileen Heckart

Film Details

Technical Specs

Synopsis

Beauregard "Bo" Decker, a rambunctious young cowboy, leaves his Montana ranch for only the second time in his life to participate in the big rodeo in Phoenix. Bo is accompanied by the more worldly Virgil, who has shepherded him through his first twenty-one years. After boarding the bus bound for Phoenix, Virg offers Bo some fatherly advice about dealing with women. When the inexperienced Bo declares that he is "gonna find me a angel," Virg advises him to settle for a "plain old little girl." As the bus nears Phoenix, Carl, the driver, stops at Grace's Diner for breakfast. As Carl flirts with the tart-tongued Grace, Bo gulps down a quart of milk and three raw hamburgers. When Elma, a young girl who works at Grace's, boards the bus, Virg encourages Bo to court her, but Bo is not interested. In Phoenix, Bo is bowled over by the big city and its teaming masses. Across from their hotel room, Virg spots the alluring Cherie dancing at the Blue Dragon Club. When the club owner insults Cherie by calling her an ignorant hillbilly, Cherie, who aspires to be a great "chantoosie," shows her waitress friend Vera a map featuring a bold red line leading from River Gulch, Cherie's home town in the Ozarks, directly to Hollywood. Soon after, Virg enters the club and Cherie cajoles him into buying her a drink. When Cherie takes the stage to warble a song, Bo bursts into the room and immediately falls in love. Proclaiming that Cherie is his angel, Bo silences the noisy crowd, follows Cherie offstage and then pulls her out the back door. Pronouncing her name "Cherry," Bo performs acrobatics to woo her, and then kisses her. After escorting Cherie back into the club, Bo proudly announces that they are engaged, much to Cherie's surprise. Cherie is dumbstruck by this turn of events, and is accused by Virg of being a cheap hustler. Early the next morning, Bo barges into Cherie's boardinghouse bedroom and, hoping to impress her with his mind, begins to recite the Gettysburg Address. Bo then hauls the sleepy Cherie to the rodeo parade and hoists her up on his shoulders. At the rodeo, Bo wraps Cherie's green scarf around his neck for luck. After winning each event, the boisterous Bo cavorts around the arena, hollering for Cherie. When Cherie, seated in the stands, tells Vera that Bo bought a marriage license and shows her an engagement ring, Vera voices concern. Spotting a preacher waiting ringside, Cherie runs away, sparking rumors about an imminent marriage between the cowboy and the sultry blonde. Back at her boardinghouse, Cherie frets as Vera packs her bags and counsels Cherie to ask for an advance on her salary so that she can make a quick getaway. At the Blue Dragon, Virg informs Cherie that Bo is a virgin who has never even been kissed. Together, Virg and Vera coach Cherie on strategies for handling Bo, but when Bo comes to collect her, Cherie, unable to lie, tells him goodbye forever. The volatile Bo then rips the tail off Cherie's costume, sending her to her dressing room in hysterics. Climbing out the window, Cherie runs to the bus station, but Bo lassoes her and drags her onto the bus bound for Montana. As the bus approaches Grace's Diner, a blizzard closes the roads, forcing the passengers to take shelter in the diner. Cherie leaves the sleeping Bo in the back of the bus, and when he awakens, he barges into the diner and harangues Cherie for leaving him behind. Outraged by Bo's behavior, Carl orders him to desist. When Bo then slings the squealing Cherie over his shoulder, Virg blocks the door and Carl challenges Bo to step outside and slug it out. After Carl soundly thrashes Bo, Virg insists that Bo apologize to everyone that he has offended. The next morning, Bo makes amends to Grace and Elma, and then meekly asks Cherie for her forgiveness and returns her scarf. When she offers him the engagement ring, Bo asks her to keep it. After news comes that the roads have opened, Cherie tries to console Bo by confessing that she was not the angel he believed her to be. As Bo and Virg prepare to board the bus, Bo asks Cherie if he can kiss her goodbye, and after a tender embrace, he runs out of the diner. Bo soon returns and shyly states that Virg has suggested that her experience and his inexperience average out, thus making them the perfect couple. Asserting that he loves her just as she is, Bo asks Cherie to marry him. Cherie, touched by his sweetness, replies that she would follow him anywhere and then throws away her map to Hollywood. Realizing that Bo no longer needs him, Virg decides to remain behind. After Bo tenderly wraps his jacket around Cherie, she drapes her scarf around his neck and he escorts her onto the bus.

Director

Joshua Logan

Cast

Marilyn Monroe

Don Murray

Arthur O'connell

Betty Field

Eileen Heckart

Robert Bray

Hope Lange

Hans Conreid

Casey Adams

Henry Slate

Terry Kelman

Linda Brace

Greta Thyssen

Helen Mayon

Lucille Knox

Kate Mackenna

George Selk

Mary Carroll

Phil J. Munch

Fay L. Ivor

Richard Culvert Johnson

William Schub

G. E. "pete" Logan

Wilbur Plaugher

Buddy Heaton

Andy Womack

J. M. Dunlap

Jim Katugi Noda

Crew

Buddy Adler

Harold Arlen

George Axelrod

Alfred Bruzlin

Charles [g.] Clarke

Ken Darby

Ken Darby

Leonard Doss

Paul S. Fox

Ben Kadish

Ray Kellogg

Mark-lee Kirk

Milton Krasner

Charles Lemaire

Harry M. Leonard

Johnny Mercer

Cyril J. Mockridge

Alfred Newman

Alfred Newman

Ben Nye

Edward B. Powell

William Reynolds

Tex Ritter

Walter M. Scott

Travilla

Helen Turpin

Lyle R. Wheeler

Photo Collections

Videos

Movie Clip

Trailer

Hosted Intro

Film Details

Technical Specs

Award Nominations

Best Supporting Actor

Articles

The Essentials-Bus Stop

Cherie (Marilyn Monroe), a sexy but no-talent "chanteuse" from the Ozarks who performs in a tacky Phoenix nightclub called the Blue Dragon, captivates the hunky but rambunctious young cowboy Beauregard "Bo" Decker (Don Murray), who is in town for a rodeo. Cherie has dreams of heading to Hollywood and film stardom, but Bo forces her to board a bus with him and his father-figure buddy, Virgil Blessing (Arthur O'Connell), as they head home to Montana. Along the way, a snowstorm stalls the bus at a lonely roadside café where Bo continues his rowdy and unwanted wooing of Cherie; he considers her his "angel" and wants to marry her. Cherie is physically attracted to Bo but repulsed by his bad behavior until, with Virgil's coaching, he begins to treat her with more tenderness and respect. Other characters interacting during the enforced layover include down-to-earth proprietor Grace (Betty Field), her bus driver lover Carl (Robert Bray) and impressionable young waitress Elma (Hope Lange).

Director: Joshua Logan

Producer: Buddy Adler

Screenplay: George Axelrod, from the play by William Inge

Cinematography: Milton Krasner

Editing: William Reynolds

Art Direction: Mark-Lee Kirk, Lyle R. Wheeler

Original Music: Alfred Newman, Cyril J. Mockridge

Costume Design: Travilla

Cast: Marilyn Monroe (Cherie), Don Murray (Beauregard "Bo" Decker), Arthur O'Connell (Virgil Blessing), Grace (Betty Field), Eileen Heckart (Vera), Robert Bray (Carl), Hope Lange (Elma Duckworth), Hans Conried (Life Magazine Photographer), Max Showalter (Life Magazine Reporter, billed as Casey Adams)

Why BUS STOP Is Essential

The movie version of Bus Stop is an adaptation of an important Broadway play by William Inge, considered by most theater historians to be among America's top playwrights. The film marked the second Inge drama to be directed by Joshua Logan, following Picnic and further establishing the reputation of this former theater director as an important filmmaker. He would go on to create such films as Sayonara (1957), South Pacific (1958) and Camelot (1967). With Bus Stop Logan and cinematographer Milton Krasner offered a lesson in the imaginative use of the often-cumbersome CinemaScope process, utilizing a subdued color palette along with a mixture of panoramic landscapes and strikingly composed close-ups. The movie launched the careers of Don Murray and Hope Lange, who continued to be prominent in the realm of film and television for several decades, and showcases the work of such fine character actors as Arthur O'Connell, Betty Field and Eileen Heckart.

Most importantly, Bus Stop marked what is generally considered to be the outstanding performance of a true American icon: Marilyn Monroe. Marilyn had already proven herself as a sensational screen presence and delightful comedienne but, as Logan wrote, her studies at the Actors Studio "had opened a part of her head, given her confidence in herself, in her brainpower, in her ability to think out and create a character." It was an audacious move for Marilyn to dare and follow the highly regarded stage performance of a theater luminary such as Kim Stanley, in a role that required her to present herself as a bedraggled, no-talent wannabe whose dreams would always be bigger than anything she could actually achieve.

Monroe's gamble paid off in spades. Whatever difficulties in achieving it, her performance shines like a beacon through a film that otherwise may seem a bit dated for modern audiences. Her needy character would certainly have benefited from a healthy dose of modern feminism, but Marilyn fully realizes and inhabits the lonely, confused and desperate Cherie without losing her own natural radiance and sex appeal. Her deliberately bad rendition of "That Old Black Magic" manages to be both awful and artful - at once pitiful, funny and erotic. Some critics felt that Monroe surpassed Stanley's highly lauded turn on Broadway.

It's simply a great performance, one that grows more impressive with repeated viewings. There was no justice in the fact that, while Murray was Oscar®-nominated for his one-dimensional, at times almost cartoon-like portrayal, Monroe was not. This was a great disappointment to many including director Logan and Monroe herself. Logan, always an ardent supporter and defender of Monroe's talent, gets the last word: "Marilyn is as near a genius as any actress I ever knew. She is an artist beyond artistry. She is the most completely realized and authentic film actress since Garbo. She has the same unfathomable mysteriousness. She is pure cinema."

By Roger Fristoe

The Essentials-Bus Stop

Pop Culture 101-Bus Stop

In August 1982 a production at the Claremont Theater in California was telecast on HBO, with Margot Kidder and Tim Matheson in the leads. The play was revived briefly on Broadway in 1996 with Mary-Louise Parker and Billy Crudup as the stars. Major regional revivals have included one at the Williamstown (Mass.) Theater Festival in the summer of 2005, and another at Boston's Huntington Theatre in the fall of 2010. Reviewing the former production in The New York Times, critic Ben Brantley wrote that, under the play's "surface glow of Eisenhower-era optimism, it also pulses with the psychosexual undercurrents in which the Freud-conscious Inge specialized." During the period 2010-2011 there were three productions in Great Britain including a critically praised version directed by James Dacre at the New Vic and Stephen Joseph Theatres. The Guardian described this production as "beguiling...[a] forlorn slice of Americana which mediates on the distance between towns and the distances between people, like an Edward Hopper painting with dialogue."

By Roger Fristoe

Pop Culture 101-Bus Stop

Trivia-Bus Stop - Trivia & Fun Facts About BUS STOP

Most of Monroe's delivery of "That Old Black Magic" was captured live on camera without lip-synching - a rarity in those days.

Don Murray has said that, in a scene where Marilyn Monroe was in bed, she was actually naked under the sheets because she thought her character would have been.

Murray, a New Yorker, had never been astride a horse until the scene in which he rides one in a parade.

In a scene where Monroe was required to angrily slap Murray with the sequined tail of her costume, she did it with such vehemence that he suffered facial lacerations. Reportedly, for whatever reason, she refused to apologize.

Because Monroe felt there should not be two blondes in the film, Hope Lange's naturally fair hair was darkened to a light shade of brown.

Murray, who was in love with Lange and would shortly marry her, has a scene on the bus where he gives her a disinterested look and says to Arthur O'Connell: "She's purty, Virge, but she ain't my angel."

Executives at 20th Century Fox thought Murray was overplaying his boisterous part and wanted to fire him. Director Joshua Logan stood firm: "I don't want some 'aw shucks' cowboy in the role. I want Attila the Hun and that's what we've got."

Rodeo scenes were filmed at the Arizona State Fairgrounds in Phoenix.

Upon returning to Los Angeles for further filming after working in skimpy clothing in the cold of Sun Valley, Monroe came down with bronchitis and then pneumonia and was hospitalized for 12 days.

Two years after Monroe played the role originated onstage by Kim Stanley, Stanley starred in The Goddess (1958) as a thinly disguised version of Monroe.

For some early television prints, the title of Bus Stop was changed to The Wrong Kind of Girl.

Quotes from Bus Stop: "I hear your name and I'm aflame..." -- Cherie (singing "That Old Black Magic")

"You don't have the manners they gave a monkey! I hate you and I despise you! Now give me back my tail!" - Cherie

"Wake up, Cherie! It's nine o'clock - the sun's out. No wonder you're so pale and white." - Bo

"I just got to feel that whoever I marry has some real regard for me, aside from all that lovin' stuff." - Cherie

"At first I thought she wasn't good enough for you. But now know you're the one who's not good enough for her!" - Virgil

"Virge has been figuring things out. He says that seeing as you had all those other boyfriends before me, seeing as I never even had one single gal friend before you... He figures it averages out to things being proper and right." - Bo

"Well, I've been thinkin' about them other fellas, Cherie. And well, what I mean is, I like you the way you are, so what do I care how you got that way?" - Bo

"Bo! That's the sweetest, tenderest thing anyone ever said to me." -- Cherie

"I'd go anywhere in the world with you now. Anywhere at all!" - Cherie

By Roger Fristoe

Trivia-Bus Stop - Trivia & Fun Facts About BUS STOP

The Big Idea-Bus Stop

Marilyn Monroe, at the height of her stardom at 20th Century Fox after her huge successes in the musical Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) and the comedy The Seven Year Itch (1955), had resented some of the thankless vehicles Fox had selected for her, notably River of No Return and There's No Business Like Show Business (both 1954). Weary of her Hollywood image as none-too-bright sex symbol, she fled to New York, where she studied acting with Lee Strasberg of the famed Actors Studio.

Before returning to Hollywood Monroe was able to renegotiate her contract with Fox, signing a deal that allowed approval of story material, director and cinematographer on her films. This agreement gave her unprecedented creative control and set a new standard for film stars. In tacit recognition of her position as the studio's top box-office draw, Fox also raised her salary to $100,000 per film and agreed that she could appear in films with independent producers and other studios. Monroe signed her fourth and final contract with the studio on December 31, 1955. In the meantime she had formed Marilyn Monroe Productions in association with photographer Milton Greene; she was to star in films produced by the company and he was to attend to all related business matters. The first film the company produced for Fox was Bus Stop, which Greene had purchased expressly for Monroe.

Monroe returned to Hollywood in February 1956 to begin preparing for the film. At a press conference announcing the project, she seemed newly serious in an uncharacteristic dark suit with a high collar. Asked if her attire was part of an effort to present "a new Marilyn," she pertly replied, "Well, I'm the same person. It's just a new suit." Announced as director was Joshua Logan, then primarily known for his work on the stage with such hits as Mister Roberts and South Pacific, although he had made an Oscar®-nominated debut as a film director with Inge's Picnic (1955). Logan wrote in his memoirs that his initial reaction to the casting idea was "Oh, no - Marilyn Monroe can't bring off Bus Stop. She can't act." After working with his star, however, he had a complete change of heart and claimed that he "could gargle with salt and vinegar" over his words because "I found her to be one of the greatest talents of all time."

Inge's play was adapted for the screen by George Axelrod, a specialist in edgy comedy who would later win acclaim for his screenplays for Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961) and The Manchurian Candidate (1962). Axelrod had become a friend of Monroe while adapting his play The Seven Year Itch as a movie vehicle for her. He commented later that he saw a tragic element in both Marilyn and her Bus Stop character, and that he tried to bring shadings of pathos as he rewrote the role with her in mind. In his screenplay Axelrod both expanded and streamlined Inge's play, which had been set entirely in the bus stop diner. Axelrod included scenes at the Blue Dragon saloon and the rodeo, as well as on the streets of Phoenix and aboard the bus itself. To keep the focus more on Cherie and Bo, Axelrod eliminated one of the play's major characters - an aging, alcoholic college professor with a weakness for young girls.

Don Murray, in his film debut at age 26, was cast as Monroe's love interest after Logan saw the then-unknown young actor performing in Thornton Wilder's The Skin of Our Teeth on Broadway. Hope Lange, then dating and later to marry Murray, also made her film debut in Bus Stop. For other key supporting roles Logan turned to two members of his cast for the film of Picnic, Arthur O'Connell and Betty Field. A new character, Cherie's confidante Vera, was invented by Axelrod for the early scenes, and the outstanding character actress Eileen Heckart was assigned the part.

From all reports, Monroe felt that this would be her most important role and provide a real stretch for her as an actress. She was eager to draw upon what she had absorbed from her studies of Method acting in playing her lonely and confused character, and to prove to her studio that they had made a good decision in giving her the artistic freedom to choose her own vehicles and colleagues.

By Roger Fristoe

The Big Idea-Bus Stop

Behind the Camera-Bus Stop

Monroe felt that Cherie, although she is a very sexual character, should have a slightly shabby look as a pale and cheaply costumed saloon singer. Working with Milton Greene, director Joshua Logan and her makeup artist, Allan Snyder, she opted for an almost-white facial and body makeup that made Cherie look washed-out and faintly unhealthy, as if she slept all day and avoided the sun. Hairstylist Helen Turpin changed Monroe's platinum-blonde hair to a subdued honey-blonde that offered more contrast to the white skin. Studio executives thought Marilyn should always be "honey-colored" all over, but she and Logan stuck to their guns. In subsequent films she would continue to favor a lighter, more luminous makeup even when her hair was once again platinum.

Monroe rejected most of the original costume designs by Travilla and rifled through the studio costume department to find things she thought suited the character. The black-lace blouse that she wears in the early scenes was originally worn by Susan Hayward in With a Song in My Heart (1952). Logan recalled how Monroe accepted the studio-designed outfit for her musical number, "That Old Black Magic," but then exclaimed to him, "You and I are going to shred it up, pull out part of the fringe, poke holes in the fishnet stockings, then have 'em darned with big, sprawling darns. Oh, it's gonna be so sorry and pitiful it'll make you cry!"

Monroe, who had seen and loved Kim Stanley's performance in the Broadway production of Bus Stop, patterned her accent on Stanley's and on those she had heard during her own time in the South. She worked diligently on the "hillbilly" twang, speaking quite differently than in other films, and subverted her natural singing talent to make it painfully clear that Cherie was not gifted in that department.

Despite her dedication and determination, however, Monroe remained hampered by her insecurities once the camera started rolling. Some of this she was able to channel creatively into the character's own confusion and uncertainty; at other times she had great difficulty in simply getting through a scene and remembering the lines. Screenwriter George Axelrod, although very fond of Monroe, was quite blunt about her problems in an interview with Pat McGilligan: "Poor Marilyn... She was a sad, sad, sad creature. She was sick. In a rightly ordered world, she would have been in a nuthouse. She was psychotic. Once you got to know her, one couldn't feel sexy about her. She was pathetic, sad. You just wanted to comfort her, cuddle her, father her, say, 'It's going to be all right, child.'"

When going up in her lines, Axelrod said, Monroe wouldn't improvise her way around them but would become emotional and leave the set. "She had reached a point in her neurosis where if anybody said, 'Cut!' she took it as an affront, burst into tears and ran to her dressing room. So director Joshua Logan stopped using the word and simply let the cameras run while he talked her back into the scene, with dialogue director Joe Curtis feeding Monroe her lines. "He was a huge man, Josh," Axelrod recalled, "so most of the time the screen was filled with Josh's behind and Marilyn's face, with this voice coming from the sky reading the lines that Marilyn would parrot."

Special problems were created in a scene on the bus, with Cherie pouring her heart out to Hope Lange's Elma as rear projection creates the illusion of a moving landscape. It took four days to shoot this scene, but Axelrod said it "cut together like a dream," partly because Lange behaved so professionally and was always prepared for a reaction shot that could cover Monroe's lapses. "Little pieces of what Marilyn would do were inspired, magical, but interspersed with tears and "Oh, ----!" and "What the ----!" and getting her back together - all of it with the camera running because you couldn't say cut. God, the goings-on!" Logan recalled, however, how brilliant Monroe was in the sequence, so involved with the emotions of her character that her skin visibly flushed and she shed real tears. As it turned out, much of this sequence was cut from the final film, deleting what Monroe felt were some of her best acting moments. She never quite forgave Logan or the studio for the cuts.

Don Murray also later remembered the difficulties of filming with Marilyn, who was essentially his boss on the movie. Paula Strasberg, Lee's wife, had replaced Natasha Lytess as Monroe's on-the-spot acting coach, and Murray recalled to Ezra Goodman that, while Strasberg was "polite," she constantly "huddled" with Marilyn and paid no attention to anyone else. Murray said that, because of Monroe's problems with lines, every scene with her was "difficult... On some scenes there would be 30 takes. The average film scene requires about five takes. If Marilyn was having trouble getting through a particular scene, and finally got it, they would print it. It did not matter how the other actors did. I had a feeling of relaxation doing the scenes she wasn't in... She was detached, into herself. On the set, she appeared frightened, worried. Just thinking about what she had to do. There was not much interchange."

There were, however, some lighter moments on the set when Monroe would tickle Murray with her unique perspective of matters. In another interview he recalled a scene in which director Logan wanted a "two-head close-up" shot, one of the first in the CinemaScope process being used for the film. Because of the width of the image, the top of Murray's head was out of the frame. "The audience won't miss the top of your head, Don," Marilyn explained. "They know it's there because it's already been established." Another laugh came when Murray mistakenly used the word "scaly" in a scene and Monroe told him it had been "a Freudian slip" because the scene had a sexual connotation. "You see," she continued, "you were thinking unconsciously of a snake. That's why you said 'scaly.' And a snake is a phallic symbol. Do you know what a phallic symbol is, Don?" Murray's reply: "Know what it is? Hell, I've got one!"

Overall, however, Murray's quoted reaction to Monroe was not one of amusement: "Like children, she thought the world revolved around her and her thoughts. She was oblivious to the needs of people near her, and her thoughtlessness, such as being late frequently, [was] the bad side of it." Once filming was over, the two never saw each other again nor had any other contact. As it developed, the warm and friendly Eileen Heckart was the only other actor in the film with whom Monroe appeared to have developed a close rapport off-camera.

Murray's view seems to have mellowed with time. At a tribute to Monroe in August 2012, he quoted Marilyn's famous line, "I don't care about being famous; I just want to be wonderful." He then called her "the most incandescently unforgettable star in the history of the movies. And if you see her as the talent-challenged singer in Bus Stop, you'll see that, while movie lovers like you have made her famous, she has achieved her greatest ambition and made herself wonderful."

Monroe's badly needed champion on the film was her director. Logan, who had studied with Stanislavsky in Russia, understood the needs of actors using "the Method" and had come to adore Marilyn's talent and to respect her native intelligence. "She made directing worthwhile," he said later. "She had such fascinating things happen to her face and skin and hair and body as she read lines, that she was... inspiring." Logan involved his star in script discussions and supported her efforts to "find" Cherie through experiments with makeup, costuming, hairstyles and - above all - intense identification with her character. By allowing the cameras to continue rolling, he gave Monroe every opportunity to find continuity in her role, and listened carefully when she made suggestions about her blocking and camera angles on this, her 24th film. As a friend of the Strasbergs who had directed their daughter, Susan, in Picnic, he was tolerant of Paula's presence and constant influence on Monroe's performance. He did, however, insist that she not be on the sets during actual rehearsals or filming.

Since Logan also was a hypersensitive soul bothered by insomnia and exhaustion, he was sympathetic to Marilyn's personal problems and creative struggles. In later years he described her as a great actress, a combination of Greta Garbo and Charlie Chaplin. "She was the most constantly exciting actress I ever worked with, and that excitement was not related to her celebrity but to her humanness, to the way she saw life around her." In a 1983 interview with Logan, this writer complimented him on his handling of William Inge's Picnic. "Oh, but didn't you like Bus Stop better?" he asked. "I did, because it had - Marilyn!"

By Roger Fristoe

Behind the Camera-Bus Stop

Critics' Corner-Bus Stop

"In Bus Stop Marilyn Monroe effectively dispels once and for all the notion that she is merely a glamour personality..." - The Saturday Review

"This is Marilyn's show and, my friend, she shows plenty in figure, beauty and talent." - Los Angeles Examiner

"In Bus Stop she has a wonderful role and she plays it with a mixture of humor and pain that is very touching." - New York Herald Tribune

"Marilyn Monroe gives one of her best performances in Bus Stop, a movie that is also one of her best overall...[She] got to stretch her acting muscles playing a fully three-dimensional character, while 20th Century-Fox still got what they wanted also, namely Monroe very sexy in a highly exploitable part...a slight, sweet, funny, and even sexy character study-romance... She is alternately bemused, annoyed, appalled, yet always attracted to Murray's dumb but handsome, sincere, and ultimately charming cowboy." -- Stuart Galbraith IV, dvdtalk.com (2013)

Awards and Honors - BUS STOP

Academy Award nomination: Don Murray, Best Supporting Actor

Golden Globe nomination: Marilyn Monroe, Best Motion Picture Actress, Comedy/Musical

Directors Guild of America nomination: Joshua Logan, Outstanding Directorial Achievement

Writers Guild of America nomination: George Axelrod, Best Written American Comedy

National Board of Review: Top Ten Films of 1956

Critics' Corner-Bus Stop

Bus Stop

Living in a spotlight that intense had its price: there was no way to step back out of the spotlight. She lost her privacy. Every move she took was photographed, celebrated, analyzed, consumed, even ridiculed. Case in point: she had enrolled in Lee Strasburg's fabled Actor's Studio to study "The Method." The movie press collectively laughed -- look at the dumb blonde who thinks she can act! "Will acting spoil Marilyn Monroe?" the headlines crowed.

It's not like she hadn't been a dramatic actress before. She had already played it straight in Fritz Lang's Clash by Night (1952), but that had been a supporting role predating her massive pop cultural breakthrough. For those who knew her only as the cartoon sex bomb of The Seven Year Itch (1955), such credits meant little. She had a headlining dramatic part in the low-budget noir thriller Don't Bother to Knock (1952), but that had been belittled by critics of the time (and only recently rehabilitated in hindsight as a fine performance in a clever film). To break the stereotypes, Marilyn Monroe needed to escape the small-mindedness of studio bosses.

Monroe took steps to prove that she meant it. She legally changed her name to Marilyn Monroe, as if to prove she was no poseur. She was Marilyn Monroe. Then she renegotiated her contract with 20th Century Fox to assert control over her films. From now on, she would choose the scripts, the directors, the technicians. She formed Marilyn Monroe Productions, with herself as President, to administer these new responsibilities.

The first film to be made under this new arrangement was Bus Stop (1956). On Broadway, William Inge's play had been a huge and long-running hit, even nominated for a Tony. Inge was a prestigious playwright -- not unlike Arthur Miller, who at the time was holed up in Nevada, trying to establish residency so he could divorce his wife and be free to wed Marilyn.

Bus Stop had a lot to offer Marilyn in her bid to bridge the gap between Movie Star and Serious Actress. The female lead, Cherie, is an aspiring actress and a terrible singer. "I'm a chanteuse," she says, with her Southern twang making "chanteuse" sound faintly obscene. Cherie has slept her way to the very bottom, but still holds impossible hopes that her dead-end job at a Phoenix saloon is just a way station on the way to stardom in Hollywood. One day. She is, in short, a shopworn sexpot, who does not even realize her best days are already behind her. And therein lies the irony--Marilyn Monroe, playing someone who wants to be like Marilyn Monroe but isn't. How better for Marilyn to demonstrate she could play someone other than herself?

She handpicked as her director Joshua Logan, a man better known for his work on such stage hits as South Pacific and Picnic. He had, in fact, directed the film adaptation of Picnic, which had opened in theaters just as the stage version of Bus Stop opened in New York, with Actor's Studio alum Kim Stanley in the role Monroe would play onscreen. Logan, though, was wary of the New Marilyn. The "old" Marilyn was a notorious flake--always late, unable to remember her lines. Was Marilyn 2.0 a worthwhile upgrade, or did it burden an already buggy system with unnecessary new features? Strasburg confided in Logan that of the hundreds of actors who had studied with him, there were only two he thought really stood out from the pack. Marlon Brando and Marilyn Monroe. This was high praise indeed.

Together they developed Cherie as a cruel parody of Marilyn's screen image. Her skin is as chalky as a vampire's, to show how the poor girl's nocturnal life denies her sunlight. Her wardrobe is tawdry and threadbare, her hair tousled and unkempt. She moves like a gangly puppet, her voice is grating. Fox executives watched nervously, as she studiously undermined everything audiences came to expect from her.

It did not come easily. Logan tried to accommodate her chronic unreliability, but she leaned heavily on that patience and strained it to the breaking point. And then, she strained it past the breaking point. With hundreds of thousands of dollars at stake if she didn't get on set now, Logan dragged her forcibly in a humiliating moment she could not forgive. Meanwhile, newcomer Don Murray, playing opposite Monroe, found himself on the receiving end of her tantrums. It made for a tense set, dominated by mutual hostility and unrelieved antagonism.

Had Bus Stop been a different movie, such on-set stress could have helped establish the on-screen mood. That is, had Bus Stop played its drama as a horror movie. The stuff of a horror movie is all there: Don Murray plays a naïve but physically intimidating young man, named Bo Decker, whose sheltered life on his cattle ranch has left him with no understanding of other people, certainly not of girls. He's used to asserting his will on other creatures, and simply cannot comprehend that there is anything else to life. When his friend Virgil (Arthur O'Connell) tries to explain that maybe Cherie resents being hogtied like a farm animal and hauled against her will onto a bus for a life of forced servitude, Bo is bewildered: "How else was I gonna get her on the bus?" He is huge and strong, heedless of social graces and unconcerned what anyone else thinks of him. He is a sort of monster, and his relentless pursuit of Cherie has similarities to various film noir tales of kidnappers and hostages--Ida Lupino's The Hitch-Hiker (1953) for example. Those connotations are there, undeveloped. At no point does Logan attempt to explore the thriller aspects of the story he has in front of him.

This is partly because Murray plays the role for laughs. He yells every line, and swaggers through each scene as if the Beverly Hillbillies' Jethro had been jacked up on coke and let loose. Cherie admits to finding this human freakshow physically attractive; Bo is insulted that she isn't equally attracted to his mind. To demonstrate his intellectual side, he blusters into her bedroom, wakes her up, pins her naked body under his, and screams the Gettysburg Address into her ear. The scene's absurdity masks its terror--Bo is just this side of raping her, but instead of sexual violence, he's hollering a piece of grade-school recital. The audience laughs nervously, because there's nothing to laugh at.

Instead, the story of Bus Stop is not about Cherie's attempt to escape this brute, but her complete inability to escape him. Bo is the sort of fella who won't take "no" for an answer, so the fact that Cherie can only muster up a half-hearted and ambivalent "no" doesn't deter him at all. At every juncture, she continues to beckon him on. She doesn't really want to be tied up, kidnapped, forcibly married, and abducted to an almost uninhabited wilderness...but neither is she entirely against the idea. Because of all the things she wants, being loved -- truly loved -- is the one she wants most, and say what you will about this big lug, he really wants her.

Despite these touches, Bus Stop isn't a thriller. Although Murray plays his role with a broadness that veers into slapstick farce, it isn't a comedy. There are a couple of songs, but it's not a musical. It builds to a mythical fight between cowboys staged at a remote Western outpost, but it isn't a Western. It's hard to say exactly what it is--other than a self-consciously serious vehicle for a self-consciously serious actress.

Marilyn Monroe's career gamble paid off as critics embraced Marilyn 2.0. Setting aside the fractiousness of the shoot, Logan praised her as being "as near genius as any actress I ever knew." Bosley Crowther, the influential and hard-to-please critic for the New York Times opened his review: "Marilyn Monroe has proved herself as an actress." Her performance in Bus Stop was widely praised, but it was costar Murray who got the Academy Award nomination (for Best Supporting Actor), which must have burned a little. Prone to seeing betrayal and intrigue all around her, Monroe was already seething that her best work on Bus Stop had been obscured from the public. The scene in question took place on board the bus, as Cherie confided in a fellow passenger (played by Hope Lange) about her deepest hopes. It was a set-up all but calculated to push Monroe's anxieties to the limit. For one thing, she feared that the deliberately anti-glamorous look she had concocted for Cherie was ruining her sex appeal, and had taken to flirting with Murray in an effort to convince herself she still "had it." But Murray had fallen for Lange -- they were soon married--and so any interaction with Lange chafed Monroe's rawest nerves.

There was another problem. The scene called for Monroe to deliver a long monologue, which needed to be filmed in a single take without cutaways. Never before had the actress successfully delivered so long of a speech at one time. It went as you would expect: Logan started the camera, called "action," Marilyn started talking -- and then would fumble. A misspoken word, a misplaced inflection, a misdirected gesture, something. Logan would call "cut!" and the cycle began anew. Nerves frayed, the day trickled away, and gradually Logan noticed something. Marilyn was more likely to screw it up at the top of the scene, and got better as it went. That first instant, as the camera starts up, was piquant with expectation -- and that was a psychological flashpoint for the fragile actress. Once past that initial burst of expectation, she settled down. So Logan figured whatever he wasted in excess filmstock would be paid for by saved time, and just stopped calling "cut." Instead, he let the camera roll, and allowed Marilyn to restart again and again on her own, until she nailed it. At the pace they'd been going, she might have taken days to get it right; Logan had gotten it from her in hours.

And then Fox executives snipped it from the film. Bus Stop was overlong, they said, and the scene dragged things to a crawl during an otherwise taut sequence. Monroe fumed that Logan would allow her triumph, so hard won and dear, to be discarded like that. Privately, Arthur Miller was growing worried that Marilyn's mood swings and self-destructive tendencies were manifesting as a genuine suicidal risk. History, tragically, would prove him right. But that was still in the future -- first, she was going to save him.

1956 was the pitch of the Red Scare, you see, and the sage lawmakers of the most powerful nation on Earth decided that they urgently needed to interview this playwright about his political beliefs. Others had faced HUAC's paranoid wrath before, and learned that there were but two painful options. Either you 1) refused to answer questions, and appeared to be a traitorous Commie or 2) you ratted out your friends as traitorous Commies. Miller was an honorable man and he thought he'd figured out a third way: be honest about his own past involvement with leftist causes, but refuse to name others. His lawyers urged him to reconsider. They saw his strategy as simply a more foolish version of Choice #1. In the end, Miller lucked into a genuine third way, entirely by accident: he mentioned he was engaged to Marilyn Monroe. HUAC let him go, and instead of an angry press tarring him as un-American, he rode a wave of happy PR. Commies are Commies, but dammit, man, this is Marilyn we're talking about! Yeah, she was All That, and Bus Stop proved she had surprises yet in store.

Producer: Buddy Adler

Director: Joshua Logan

Screenplay: George Axelrod (screenplay); William Inge (play)

Cinematography: Milton Krasner

Art Direction: Mark-Lee Kirk, Lyle R. Wheeler

Music: Cyril J. Mockridge, Alfred Newman

Film Editing: William Reynolds

Cast: Marilyn Monroe (Cherie), Don Murray (Beauregard 'Bo' Decker), Arthur O'Connell (Virgil Blessing), Betty Field (Grace), Eileen Heckart (Vera), Robert Bray (Carl), Hope Lange (Elma Duckworth), Hans Conried (Life Magazine Photographer), Casey Adams (Life Magazine Reporter).

BW-96m. Letterboxed.

by David Kalat

Sources:

Sam Kashner and Jennifer Macnair, The Bad and the Beautiful: Hollywood in the Fifties.

Barbara Leaming, Marilyn Monroe.

Carl Edmund Rollyson, Marilyn Monroe: A Life of the Actress.

J. Randy Taraborelli, The Secret Life of Marilyn Monroe.

Bus Stop

TCM Remembers - Eileen Heckart

Eileen Heckart, who won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for Butterflies Are Free (1972), died December 31st at the age of 82. Heckart was born in 1919 in Columbus, Ohio and became interested in acting while in college. She moved to NYC in 1942, married her college boyfriend the following year (a marriage that lasted until his death in 1995) and started acting on stage. Soon she was appearing in live dramatic TV such as The Philco Television Playhouse and Studio One. Her first feature film appearance was as a waitress in Bus Stop (1956) but it was her role as a grieving mother in the following year's The Bad Seed that really attracted notice and an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress. Heckart spent more time on Broadway and TV, making only occasional film appearances in Heller in Pink Tights (1960), No Way to Treat a Lady (1968) and Heartbreak Ridge (1986). She won one Emmy and was nominated for five others.

TCM REMEMBERS DAVID SWIFT, 1919-2001

Director David Swift died December 31st at the age of 82. Swift was best-known for the 1967 film version of the Broadway musical, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying (he also appears in a cameo), Good Neighbor Sam (1964) starring Jack Lemmon and The Parent Trap (1961), all of which he also co-wrote. Swift was born in Minnesota but moved to California in the early 30s so he could work for Disney as an assistant animator, contributing to a string of classics from Dumbo (1941) to Fantasia (1940) to Snow White (1937). Swift also worked with madcap animator Tex Avery at MGM. He later became a TV and radio comedy writer and by the 1950s was directing episodes of TV series like Wagon Train, The Rifleman, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Playhouse 90 and others. Swift also created Mr. Peepers (1952), one of TV's first hit series and a multiple Emmy nominee. Swift's first feature film was Pollyanna (1960) for which he recorded a DVD commentary last year. Swift twice received Writers Guild nominations for work on How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying and The Parent Trap.

TCM REMEMBERS PAUL LANDRES, 1912-2001

Prolific B-movie director Paul Landres died December 26th at the age of 89. Landres was born in New York City in 1912 but his family soon moved to Los Angeles where he grew up. He spent a couple of years attending UCLA before becoming an assistant editor at Universal in the 1931. He became a full editor in 1937, working on such films as Pittsburgh (1942) and I Shot Jesse James (1949). His first directorial effort was 1949's Grand Canyon but he soon became fast and reliable, alternating B-movies with TV episodes.. His best known films are Go, Johnny, Go! (1958) with appearances by Chuck Berry and Jackie Wilson, the moody The Return of Dracula (1958) and the 1957 cult favorite The Vampire. His TV credits run to some 350 episodes for such series as Adam 12, Bonanza, Death Valley Days and numerous others. Landres was co-founder in 1950 of the honorary society American Cinema Editors.

BUDD BOETTICHER 1916-2001

When director Budd Boetticher died on November 29th, American film lost another master. Though not a household name, Boetticher made crisp, tightly wound movies with more substance and emotional depth than was apparent at first glance. Instead of a flashy style, Boetticher preferred one imaginatively simple and almost elegant at times. Because of this approach films like The Tall T (1957), Decision at Sundown (1957), The Bullfighter and the Lady (1951) and Ride Lonesome (1960) have withstood the test of time while more blatantly ambitious films now seem like period pieces.

Budd was born Oscar Boetticher in Chicago on July 29th, 1916. With a father who sold hardware, Boetticher didn't come from a particularly artistic background. In college he boxed and played football before graduating and heading to Mexico to follow what's surely one of the most unusual ways to enter the film industry: as a professional matador. That's what led an old friend to get Boetticher hired as a bullfighting advisor on the 1941 version of Blood and Sand. Boetticher quickly took other small jobs in Hollywood before becoming an assistant director for films like Cover Girl. In 1944, he directed his first film, the Boston Blackie entry One Mysterious Night. Boetticher made a series of other B-movies, like the underrated film noir Behind Locked Doors (1948), through the rest of the decade.

Boetticher really hit his stride in the 50s when he began to get higher profile assignments, including the semi-autobiographical The Bullfighter and the Lady in 1951 which resulted in Boetticher's only Oscar nomination, for Best Writing. Sam Peckinpah later said he saw the film ten times. Other highlights of this period include Seminole (1953) (one of the first Hollywood films sympathetic to American Indians), the stylishly tight thriller The Killer Is Loose (1956) and the minor classic Horizons West (1952). In the late 50s, Boetticher also started directing TV episodes of series like Maverick and 77 Sunset Strip.

In 1956, Boetticher started a string of films that really established his reputation. These six Westerns starring Randolph Scott are known as the Ranown films after the production company named after Randolph Scott and producer Harry Joe Brown. Actually the first, Seven Men from Now (1956), was produced by a different company but all of them fit together, pushing the idea of the lone cowboy seeking revenge into new territory. The sharp Decision at Sundown twists Western cliche into one of the bleakest endings to slip through the Hollywood gates. The Tall T examines the genre's violent tendencies while Ride Lonesome and Buchanan Rides Alone (1958) have titles appropriate to their Beckett-like stories. The final film, Comanche Station, appeared in 1960.

That was the same year Boetticher made one of the best gangster films, The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond, before watching everything fall apart. He and his wife decided to make a documentary about the famous matador Carlos Arruza and headed to Mexico. There Boetticher saw Arruza and much of the film crew die in an accident, almost died himself from an illness, separated from and divorced his wife (Debra Paget), and then spent time in various jails and even briefly a mental institution. This harrowing experience left him bankrupt but he still managed to complete the film, Arruza (1968), which gathered acclaim from the few who've been able to see it.

Boetticher managed to make just one more film, My Kingdom For... (1985), a self-reflexive documentary about raising Andalusian horses. He also made a cameo appearance in the Mel Gibson-Kurt Russell suspense thriller, Tequila Sunrise (1988). He died from complications from surgery at the age of 85.

By Lang Thompson

TCM Remembers - Eileen Heckart

George Axelrod, 1922-2003

Born June 9, 1922, in New York City to the son of the silent film actress Betty Carpenter, he had an eventful childhood in New York where, despite little formal education, he became an avaricious reader who hung around Broadway theaters. During World War II he served in the Army Signal Corps, then returned to New York, where in the late 40's and early 50's he wrote for radio and television and published a critically praised novel, Beggar's Choice.

He scored big on Broadway in 1952 with The Seven Year Itch. The comedy, about a frustrated, middle-aged man who takes advantage of his family's absence over a sweltering New York summer to have an affair with a sexy neighbor, won a Tony Award for its star, Tom Ewell, and was considered daring for its time as it teased current sexual mores and conventions. The play was adapted into a movie in 1955 by Billy Wilder, as a vehicle for Marilyn Monroe, with Ewell reprising his role. Unfortunately, the censors and studio executives would not allow the hero to actually consummate the affair; instead, Ewell was seen merely daydreaming a few romantic scenes, a situation that left the playwright far from happy.

Nevertheless, the success of The Seven Year Itch, opened the door for Axelrod as a screenwriter. He did a fine adaptation of William Inge's play Bus Stop (1956) again starring Marilyn Monroe, and did a splendid job transferring Truman Capote's lovely Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961). Although his relationship with the director Blake Edwards was rancorous at best, it did earn Axelrod his only Academy Award nomination.

So frustrated with his work being so heavily revised by Hollywood, that Axelrod decided to move from New York to Los Angeles, where he could more closely monitor the treatment of his scripts. It was around this period that Axelrod developed some his best work since he began producing as well as writing: the incisive, scorchingly subversive cold war thriller The Manchurian Candidate (1962), based on Richard Condon's novel about an American POW (Laurence Harvey) who returns home and is brainwashed to kill a powerful politician; the urbane comedy Paris When it Sizzles (1964) that showed off its stars William Holden and Audrey Hepburn at their sophisticated best; his directorial debut with the remarkable (if somewhat undisciplined) satire Lord Love a Duck (1966) that skewers many sacred institutions of American culture (marriage, school, wealth, stardom) and has since become a cult favorite for midnight movie lovers; and finally (his only other directorial effort) a gentle comedy of wish fulfillment The Secret Life of an American Wife (1968) that gave Walter Matthau one of his most sympathetic roles.

By the '70s, Axelrod retired quietly in Los Angeles. He returned to write one fine screenplay, John Mackenzie's slick political thriller The Fourth Protocol (1987) starring Michael Caine. He is survived by his sons Peter, Steven, and Jonathan; a daughter Nina; seven grandchildren; and a sister, Connie Burdick.

by Michael T. Toole

George Axelrod, 1922-2003

Quotes

I hate you and I despise you! Now give me back my tail!- Cherie

I just got to feel that whoever I marry has some real regard for me, aside from all that lovin' stuff.- Cherie

Trivia

Marilyn Monroe objected to the color of Hope Lange's hair, claiming that it was too fair and detracted from her own. As a result, Lange's hair was darkened.

'Murray, Don' suffered painful facial cuts when Monroe over-did a scene in which she had to slap him with the sequined tail of her costume.

Notes

This picture marked Marilyn Monroe's return to the screen after a one-year absence. Monroe was dissatisfied with the roles that Twentieth-Century Fox assigned to her, and left Hollywood after completing The Seven Year Itch (see below). Suspended by the studio, she moved to New York where she enrolled in the Actors Studio, under the tutelage of famed acting teachers Lee and Paula Strasberg, according to a September 1956 article in Cue. After announcing the formation of Marilyn Monroe Productions, Monroe finally came to terms with Fox when the studio offered her a lucrative contract that granted her approval over directors, according to a May 1956 Hollywood Reporter news item. Bus Stop was the first picture of Monroe's new seven-year contract.

Many of the reviews commented that Monroe's New York experience had greatly improved her acting ability. The Hollywood Reporter review noted that her performance had "been augmented by a sensitivity, poignancy and apparent understanding that Miss Monroe did not display before." An October 1955 Variety news item noted that producer Buddy Adler initially wanted Montgomery Clift to play the role of "Bo." Don Murray made his screen debut in the picture and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Bo. The picture also marked the screen debut of Hope Lange (1931-2003), who married Murray during the film's production.

Although a Hollywood Reporter news item reported that Steffi Sidney was cast as a rodeo fan, her appearance in the released film has not been confirmed. Other Hollywood Reporter news items noted that the rodeo sequence was filmed on location in Phoenix, AZ during the JAYCEE World Championship rodeo, and that the exteriors for the diner scenes were shot in Sun Valley, ID. Although a July 1956 Hollywood Reporter news item stated that dramatist William Inge sued to restrain exhibition of the film until after December 1, 1956, when all the first class stage productions of his play would be closed, that suit failed and the film opened in August 1956. From 1961 to 1962, ABC television broadcast a television series entitled Bus Stop, loosely based on Inge's play, starring Marilyn Maxwell, Rhodes Reason and Richard Anderson.

Miscellaneous Notes

Voted One of the Year's Ten Best Films by the National Board of Review.

Released in United States Summer August 1956

Don Murray's film debut.

CinemaScope

Released in United States Summer August 1956

Voted One of the Year's Ten Best Films by the 1956 New York Times Film Critics.