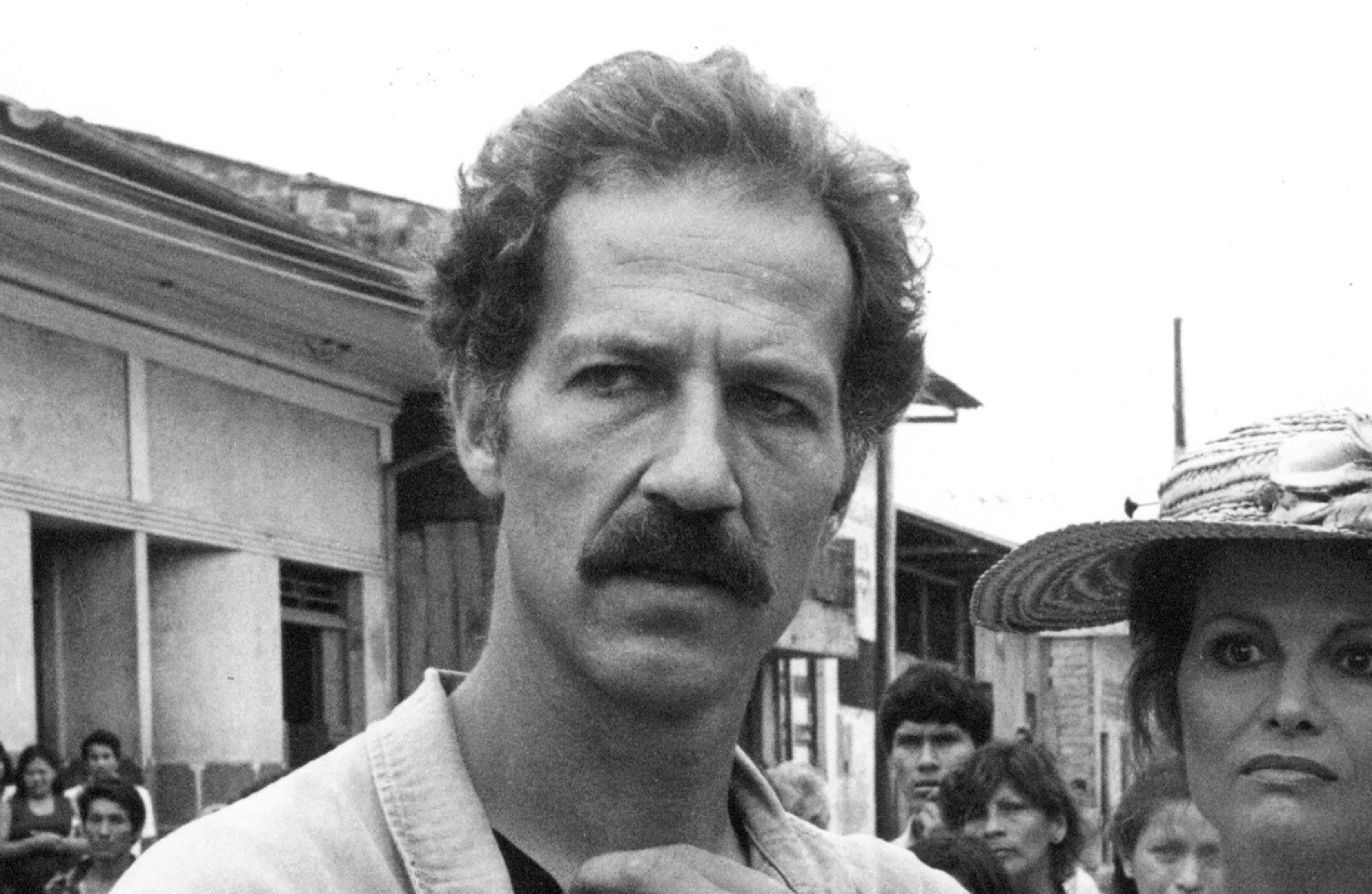

Werner Herzog

About

Biography

Filmography

Family & Companions

Notes

"I try to make films because I know that I have some sort of vision or insight . . . When I make a film I try to articulate it." For him, "it's the fire" of belief and commitment that makes the film, and goes on: "When I look back at my films I think they all came out of some sort of pain . . . I make films to rid myself of them, like ridding myself of a nightmare." It is not that he wants to "make confessions," only that for him film is "something which has more importance than my private life." --Werner Herzog, quoted in "World Film Directors", Volume Two, edited by John Wakeman

Biography

A study in both controversy and contradictions, filmmaker Werner Herzog, more than any of his peers, embodied German history, character and cultural richness in his work, while at the same time challenging previous conventions. Yet unlike his contemporaries Fassbinder, Wenders and Schlondorff, Herzog never set a significant film in his own country in his own time. Instead, his restless nature took him far and wide across the world, while his journeys to the edge of inner psychosis provided the impetus for a brand of filmmaking renowned for its physical demands on everyone involved. While growing up in the shadow of Nazi atrocities may have prompted him to probe the darker aspects of human behavior, Herzog developed a paradoxical style of realism that was part of a vision that combined 20th century Expressionism with 19th century Romanticism. Unifying these disparate elements was his elevation of the grotesque and chaotic, first by casting non-professional actors like former mental patient Bruno S. in "Stroszek" (1977), then by his tumultuous, almost violent collaboration with the explosive actor Klaus Kinski. It was with Kinski that Herzog created his finest work - "Aguirre, Wrath of God" (1972), "Nosferatu the Vampyre" (1979) and "Fitzcarraldo" (1982) - while at the same time creating ugly off-camera battles that became the stuff of cinema legend. Whether he was threatening to shoot Kinski with a rifle or briefly contemplating an offer by native South Americans to have the actor killed, Herzog's volatile relationship with Kinski took both a physical and mental toll on both. While Herzog settled into calmer waters directing such acclaimed documentaries as "White Diamond" (2004) and the Oscar-nominated "Grizzly Man" (2005) following Kinski's death in 1991, he never reached such creative and manic heights again.

Born Sept. 5, 1942 in Sachrang, Germany, outside Munich, Herzog was raised by his father, Dietrich and his Yugoslavian mother, Elizabeth, both of whom were biologists. While his mother doted on him, his father remained largely absent from the family, which led to his parents separating in 1954. Herzog moved to Munich with his mother and two brothers, Lucki and Tilbert, soon after. But his time living in a small village and taking long, lonely walks in the Bavarian mountains fueled his imagination. Inspired by an encyclopedia entry on filmmaking, Herzog began submitting film ideas to producers. He eventually made his way to Munich University, where he made prize-winning shorts like "Herakles" (1962) and "Spiel im Sand" (1964). Leaving university with a degree and a 35mm camera he liberated from the equipment room, Herzog started making his own films financed by working nights as a welder. He directed his third short, a scathing anti-war satire called "Die Bespiellose Verteidgung der Festung Deutschkreuz" ("The Unprecedented Defense of Fortress Deutschkreuz") (1966), after which he formed his own production company, Werner Herzog Film, which remained in operation the remainder of his career.

After directing another short, "Letzte Worte" (Last Words") (1967), Herzog - still using his pilfered camera - made his first feature-length film, "Leibenszeichen" ("Signs of Life") (1968), which earned him the German National Film Award for Best First Feature. Based on Achim von Arnim's short story Der Tolle Invalide auf dem Fort Ratonneau, the film depicted a lonely German soldier injured during World War II and sent to a Greek island to recuperate, only to go insane and want to blow up the entire island. Courting danger in his personal life progressed logically to a preoccupation with authentic experience as the basis for his films, a monomania resulting in Herzog's arrest as a suspected mercenary and his subsequent torture in Cameroon during the making of "Fata Morgana" (1969). Meanwhile, Herzog's already apparent obsession with insanity and the oddities of life reached new heights with "Even Dwarfs Started Small" (1970), a bizarre little film about a group of dwarfs in a mental institution who become sick of being tormented by so-called normal people and stage a coup, taking over the entire asylum and changing the status quo.

Strange as the film itself may have been, the production was even weirder, with Herzog dealing with one disaster after another - one actor was run over, but uninjured, by a runaway vehicle, while another caught fire, which Herzog put out himself. The two accidents prompted him to make a promise to jump into a cactus patch if no other harmful events occurred during production. After filming wrapped without incident, Herzog did as promised. He later said that "getting out was a lot more difficult than jumping in." Putting aside narrative films and venturing into documentaries, something that he would do frequently throughout his career, Herzog directed "Land des Schweigens und der Dunkelheit" ("Land of Silence and Darkness") (1971). The film followed Fini Strabinger, a Bavarian woman who is both blind and deaf, and makes a career trying to help others struggling with the same problem. Eschewing a voice-of-God narration in favor of letting the people he documented tell the story, Herzog crafted a moving film that was highlighted by his capturing Strabinger's first airplane ride and another deaf-and-blind man hugging a tree.

Herzog's career up to this point may have been a mere footnote in cinema history had he continued on in a similar vein. But his next feature, "Aguirre, Wrath of God" (1972), which starred the brilliant madman Klaus Kinski, solidified both director and actor into filmmaking lore. Herzog had actually known the volatile Kinski years earlier, when the then-struggling actor rented a room from Herzog's family's apartment, where his bizarre antics and deranged behavior made a lasting impression on the director. So when Herzog wrote the script for "Aguirre," he knew Kinski was the perfect choice to play Spanish soldier Lope de Aguirre, who leads a group of conquistadores down the Amazon River in search of the legendary city of gold, El Dorado, only to fall prey to folly and eventual madness. Though the film itself was nothing short of genius, "Aguirre" became infamous for what occurred during production than for the final product. While some of the more outlandish tales were stretched beyond their original truth, much of what happened between Herzog and Kinski lived on for decades in filmmaking infamy, while laying the groundwork for future insanity with four more collaborations.

Disagreeing over how to portray Aguirre, among many other things, Herzog and Kinski engaged in almost daily volcanic arguments that occasionally led to threats of violence. Angered over the director's refusal to fire a sound assistant, Kinski threatened to leave the set for good. Herzog countered by claiming he had a rifle and that eight of its bullets would find their way into Kinski, with a ninth being reserved for himself. The story gave rise to the legend that Herzog had actually directed Kinski at gunpoint, which the director vehemently and consistently denied over the years. But one incident of real violence occurred when a particularly hostile Kinski was annoyed by a group of cast and crew playing cards in a nearby hut. The explosive actor fired three shots into the hut, blowing the finger off one of the extras. But instead of trying to stamp out such behavior, Herzog actively antagonized Kinski, which led to regular outbursts that burned him out and produced the acting results he desired. Regardless of such insanity behind the scenes, which made other more famous examples of filmmaking excess pale in comparison, "Aguirre" was undoubtedly a work of profound artistry that saw two megalomaniacal creative forces come together effectively.

Unrelenting in its concentration on filth, disease and brutality, "Aguirre" functioned as an allegory of the fascistic personality, invoking both Germany's glorification of the Nazis and America's oppression of Vietnam, not to mention the general reading that bestiality often lingers beneath the facade of civilized conventions. "Aguirre" opened with an extraordinary shot of an almost endless line of conquistadors and slaves making their way down the valley in the jungle and ended with Aguirre adrift, the expedition's lone survivor, ranting and raving while floating down the Amazon on a corpse-strewn raft overrun with hundreds of twittering monkeys. In between, the maniacal conquistador used intimidation and murder to gain control of his party, declaring himself the "wrath of God" while setting off to find El Dorado, the legendary Inca city of gold. As the camera circled around the raft, reinforcing a sense of entrapment and doom, the stunning final image conjured a sense of awe, even admiration, for the heroic madman. A truly haunting visual that served as an apropos metaphor for the film's crazed and chaotic shoot.

Blending both fact and fiction, Herzog made "Jeder für Sich und Gott Gegen Alle" ("The Mystery of Kaspar Hauser") (1975), which loosely depicted the true story of a 16-year-old boy discovered standing in the town square of Nuremberg in 1828, unable to walk or talk after having been locked away in a dark cellar and deprived of all human contact since birth. Herzog's choice of former mental patient-turned-street performer Bruno S. for the title role was a stroke of genius. Prior to the film, Bruno S. was the battered, illegitimate child of a prostitute who spent his formative years in and out of mental institutions and various correctional facilities. When Herzog saw him in a documentary made about street performers, he knew instantly that the former mental patient was the perfect choice to compellingly express the injuries Kaspar Hauser had incurred at the hands of a restrictive society, establishing the authentic immediacy that was de rigueur for the director's films. After filming the documentary, "La Soufriere" (1976), for which he journeyed to an evacuated Guadeloupe island to photograph the eruption of a volcano which never occurred, Herzog made the avant-garde "Herz aus Glas" ("Heart of Glass") (1976) before reuniting with Bruno S. for "Stroszek" (1977), which took its trio of misfits (Bruno S., Eva Mattes and Clemens Scheitz) to Wisconsin in search of the American dream that quickly turns into a nightmare.

Herzog waded back into perilous waters when he cast Kinski as the titular "Nosferatu the Vampyre" (1979), a faithful remake of the classic 1922 silent film, "Nosferatu." With distribution set for the United States via 20th Century Fox, the director filmed two versions at once; one with the actors using their native German tongue and the other in English. While received well by critics, the film had trouble finding an audience in America, though it did manage to fair decently enough at the box office. Just days after "Nosferatu" wrapped shooting, Herzog employed the same exhausted crew to film an adaptation of Georg Büchner's play, "Woyzeck" (1979), which starred Kinski as an unthinking killing machine manufactured through lab experimentation whose only glimmer of humanity is loving his wife, Marie (Eva Mattes), only to find himself forced to killer her as well. Though not as well known as their other collaborations, "Woyzeck" was nonetheless another pitch-perfect examination of decent into madness that only Herzog and Kinski could conjure.

Never one to shy away from a challenge, Herzog famously ate his own sh after promising to do so if filmmaker Errol Morris finished his first documentary, "Gates of Heaven" (1980). In an effort to help drum up studio support for a theatrical release, Herzog had director Les Blank capture the moment in the short documentary, "Werner Herzog Eats His Sh " (1980). Served with garlic and German beer, Herzog took small bites before an audience awaiting the premiere of Morris' film while relaying his thoughts on how entering show business, even as a director, can turn one into a clown. Reuniting with Kinski for a fourth time, Herzog directed the ambitious, but disaster-plagued "Fitzcarrado" (1982), which may have surpassed "Aguirre" for the infamous goings-on behind the scenes. On screen, the film told the tale of an obsessed opera lover who stops at nothing to build an opera house in a remote Peruvian village cutoff by mountains and treacherous rapids. Once again, Kinski was perfectly cast as the manic obsessive who drives everyone, including himself, to the brink of madness in order to achieve his lofty goals - a characterization that aptly mirrored Herzog's own zealotry.

Three years in the making, "Fitzcarraldo," and its companion piece, "Burden of Dreams" (1983), Les Blank's behind-the-scenes documentary, were testaments to the danger and extremism of what was ultimately the defining project of Herzog's career. One of the bigger obstacles faced by the director was the monumental task of hauling a 320-ton steamboat over a mountain in an effort to again achieve aesthetic realism while throwing off the trappings of using special effects. Even before production began, he found himself in the middle of a border dispute between Peru and Ecuador, which forced him to move locations. Meanwhile, Jack Nicholson backed out before shooting began, while his replacement, Warren Oates, opted out at the last minute. During filming, co-star Jason Robards contacted am bic dysentery halfway through, while Mick Jagger withdrew to prepare for a Rolling Stones tour. But it was Kinski who offered the most problems with his daily outburst that would shut down production for hours; even days at a time. The natives Herzog employed to move the ship through the Amazon jungle came to the director with an offer to kill his manic lead actor. Though appreciative of their offer, Herzog politely declined, stating that Kinski was still needed for shooting. While the production problems mounted, including one of the laborers cutting off his own foot after being bitten by a particularly poisonous snake, Herzog's own plight mirrored Fitzcarraldo's inability to bend nature to his will.

In 1984, Herzog made two highly-acclaimed short films, "The Ballad of the Little Soldier," which drew protests from pro-Sandanistas that Herzog was in league with the Contras and the CIA, and "The Green Glow of the Mountains," which was full of the exotic scenery that served as the backdrop for Reinhold Messner and his partner Hans Kammerlander's mountain climbing heroics in Pakistan. After directing the television documentary, "Herdsman of the Sun" (1988), which chronicled the sub-Saharan Wodaabe tribe, he collaborated with Kinski on "Cobra Verde" (1988), their fifth and final film together. Widely considered to be their least desirable effort, the epic adventure about a Brazilian entrepreneur (Kinski) who g s mad while running a 19th century African plantation did not disappoint with its behind-the-scenes action. With their personal conflict reaching full fruition, Herzog and Kinski battled daily, with the actor going to great lengths to disrupt production with his volcanic outbursts. Kinski's torrent of abuse projected at cinematographer Thomas Mauch led the latter to walk off the project, forcing Herzog to find a replacement. But despite the lack of enthusiasm from audiences, critics were on the whole fairly pleased with the results. Most significantly, Kinski died four years after making the film, which marked the end to one of the most storied, volatile and creatively satisfying collaborations in cinema history.

After "Cobra Verde," Herzog settled into making mostly documentaries, while occasionally returning to narrative films. After making "Ech s of a Somber Empire" (1990), which chronicled the bizarre and increasingly paranoid last years of Jean-Bédel Bokassa's military rule of the Central African Republic, Herzog made "Lessons of Darkness" (Discovery Channel, 1992), a look at the environmental impact of the 1991 Gulf War on Kuwait. But even in documentaries, Herzog was not without controversy, as he was expelled from Kuwait by the Amirs for his depiction of the men and women who fought the oil well fires set by former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein. By this time, Herzog had ventured into directed opera, surprising for someone who claimed that he refused to listen to any music for almost a decade as a child after refusing to sing in front of class. Over the years, he directed such noted operas as "Doktor Faustus" (1986), "Giovanna d'Arco" (1989), "The Flying Dutchman" (1993) and Mozart's "The Magic Flute" (1999). Turning back to documentaries, he filmed "Little Dieter Needs to Fly" (1997), a look at German-American Navy pilot Dieter Dengler, who was shot down during Vietnam and sent to a POW camp where he suffered torture and starvation before making a brave successful escape through the perilous jungles.

For his next film, the documentary "My Best Fiend" (1999), Herzog explored the chaotic life and career of his old friend, Klaus Kinski, who once called the director a "blowhard" and a "sadistic, treacherous, cowardly creep." In rather blasé fashion, Herzog recounted the tumultuous professional and personal relationship that resulted in nasty on-set encounters and various death threats, including serious consideration by Herzog to firebomb Kinski's house. "My Best Fiend" was a hit as it made the festival rounds, including Cannes, Telluride and the Chicago International Film Festival. Herzog returned to fictional narrative with "Invincible" (2002), starring Tim Roth as the sinister owner of the Palace of the Occult in Weirmar Berlin, where a former blacksmith from Poland (Jouko Ahola) arrives to perform as a strongman. As anti-Semitism spreads and the Nazis increase their power, the strongman, plagued by nightmares, returns to Poland convinced he has been commanded by God to warn fellow Jews of the impending danger. Blending fact and fiction, Herzog eschewed a melodramatic handling of relations between Nazis and Jews and instead favored a slow and hauntingly stylized tone. In casting untrained actor Jouko Ahola as the kind-hearted, but naïve strongman, Herzog added goodness and optimism into his film, a rare feat for the typically dark and complicated director.

In his next documentary, "Wheel of Time" (2003), Herzog observed the creation of the Kalachakra Sand Mandala, or wheel of time, a collage of images representing the stages of Buddhist enlightenment. For the first eight of 12 days, Buddhist monks make the wheel from sand ground of white stone and mixed with opaque water colors. The last four days are spent initiating students and ends with the Dalai Lama thanking the 722 deities for participating, followed by sweeping away the sands. Herzog was invited by the monks to film the ritual, but he initially wanted to decline because his knowledge of Buddhism was thin at best. He eventually accepted and created a film with beautiful images, including the opening scenes of teeming crowds in saffron robes roaming the streets of Bodh Gaya, the town where Buddha sat under a tree and became enlightened, at the start of the initiation. The film proved to be another foray into gentler, more calming waters for the typically maniacal Herzog.

With "White Diamond" (2004), a documentary about airship engineer Dr. Graham Dorrington, who embarks on a trip to the Kaieteur Falls in Guyana to fly his helium-filled balloon above the trees, Herzog explored one man's unflinching will to conquer nature. Though not nearly as crazed as Kinski, Dorrington provided an element of lunacy to the effort, a common denominator in many of Herzog's films. Lurking death also factored in: 12 years prior to Dorrington's expedition, friend Dieter Plage plummeted to his death in a similar experiment. For "Grizzly Man" (2005), Herzog again ventured into the wilds to follow the path of a half-crazed man hell-bent on penetrating nature. The subject this time was Timothy Treadwell, a self-avowed grizzly bear activist who went to Katmai National Park & Preserve every summer to live with the Alaskan brown bear. Treadwell brought a camera to the refuge and documented himself over the course of five summers, usually turning the camera on himself and as his "bear friends" as he hiked through the woods.

A former alcoholic and drug user, Treadwell ultimately found his own salvation in trying to save the relatively well-protected bears that needed no protection. The activist met his ultimate fate when he stayed in the wild later than usual and encountered an old, hungry rogue bear that killed and ate Treadwell and his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard; an event that was captured while his camera was running with the lens cap on so that only audio of the grizzly attack could be heard. Herzog kept the sound of the attack to himself - the audience was only allowed to watch the director listening to the recording through headphones. Even the sometimes twisted Herzog knew immediately that Treadwell and Huguenard's horrific demise was to be kept private. With over 70 hours of Treadwell's footage at his disposal, Herzog conducted his own after-the-fact interviews to create a probing and entertaining look at a man at war with nature, human civilization and himself. Herzog ventured back to feature films with the experimental sci-fi disaster film, "The Wild Blue Yonder" (2005), which starred Brad Dourif as an extraterrestrial from a water planet who returns to Earth only to find the planet uninhabitable.

In January 2006, Herzog made a bit of news when actor Joaquin Ph nix overturned his car on Sunset Boulevard close to where the director lived. Herzog assisted the actor from his vehicle, who emerged relatively unscathed. A few days later, the director was giving an outdoor interview with Mark Kermode from the BBC, when Herzog was shot with an air rifle by an unknown assailant. Though initially shocked, Herzog quickly shrugged off the attack, declining Kermode's offer to call the police to hunt down his attacker. Later, Herzog displayed a bloodied abrasion slightly north of his groin and told an astonished Kermode that "it is not a significant bullet." Meanwhile, he directed "Rescue Dawn" (2006), a fictional account of Deiter Dengler's heroics starring Christian Bale, who was put through an ordeal almost similar as that faced by the downed pilot. He next helmed the documentary "Encounters at the End of the World" (2007), which brought audiences to McMurdo Station on Ross Island in Antarctica, where he filmed some of the most exhilarating landscapes of this remote section of Earth. Herzog next directed the off-kilter Nicolas Cage in "Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans" (2009), a not-very-faithful remake of "Bad Lieutenant" (1992), starring Harvey Keitel.

Filmography

Director (Feature Film)

Cast (Feature Film)

Cinematography (Feature Film)

Writer (Feature Film)

Producer (Feature Film)

Music (Feature Film)

Sound (Feature Film)

Misc. Crew (Feature Film)

Director (Special)

Producer (Special)

Director (Short)

Writer (Short)

Producer (Short)

Editing (Short)

Misc. Crew (Short)

Life Events

1954

After parents separation, moved to Munich with mother and two brothers

1957

Began submitting film ideas to producers at age 14

1962

Received prizes for two amateur shorts "Herakles" (1962) and "Spiel im Sand" (1964)

1966

Established Werner Herzog Film production

1967

Directed third short "Die beispiellose Verteidigung der Festung Deutschkreuz"

1968

Helmed short film "Letzte Worte/Last Words"

1968

First full length film "Leibenszeichen/Signs of Life" won the German National Film award for first feature

1970

Helmed second feature "Even Dwarfs Started Small"; filmed banned in Germany

1971

Collaborated with Leonard Cohen and Couperin (both providing music) on "Fata Morgana"

1972

First collaboration with the actor Klaus Kinski, "Aguirre, the Wrath of God"; filmed on location in Peru

1974

Chose former mental patient Bruno S. for title role of "The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser"

1977

Reteamed with Bruno S. for "Stroszek"; first collaboration with actress Eva Mattes

1979

Helmed remake of the 1922 vampire film "Nosferatu the Vampyre"; second collaboration with Kinski

1979

Filmed adaptation of Georg Buchner's 1836 play "Woyzeck"; third and last colaboration with Mattes

1982

Returned to Peru, overcoming obstacles of nightmarish proportions to complete "Fitzcarraldo" with star Kinski

1984

Helmed two short films, "The Ballad of the Little Soldier" and "The Green Glow of the Mountain"

1987

Final film with actor Kinski, "Cobra Verde"

1992

Directed the documentary "Lessons of Darkness" (Discovery Chanel)

1997

Helmed the documentary "Little Dieter Needs to Fly"

1999

Filmed documentary "My Best Fiend ¿ Klaus Kinski" about their infamous collaboration

1999

Acted in Harmony Korine's Dogma 95 film "Julien Donkey-Boy"

2001

Wrote and directed war drama "Invincible"; film premiered at the Venice Film Festival (released theatrically 2002)

2003

Helmed documentary "Wheel of Time" about the largest Buddhist ritual to promote peace and tolerance

2005

Directed documentary "Grizzly Man," about grizzly bear activists Timothy Treadwell and Amie Huguenard, who were killed October of 2003 while living among grizzlies in Alaska; earned an Independent Spirit Award Nomination for Best Documentary

2007

Directed Christian Bale in "Rescue Dawn," a film based on his acclaimed 1998 documentary "Little Dieter Needs to Fly"

2008

Filmed documentary "Encounters at the End of the World," about people and places in Antarctica; earned Independent Spirit and Academy Award nominations for Best Documentary

2009

Directed Nicolas Cage in "Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans"

2009

Directed Michael Shannon in thriller "My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done"; also co-wrote

2010

Directed historical documentary "Cave of Forgotten Dreams"

2012

Cast opposite Tom Cruise in action drama "Jack Reacher"

2013

Co-directed documentary "Happy People: A Year in the Taiga" with Dmitry Vasyukov; also co-wrote with Vasyukov and son Rudolph Herzog

Videos

Movie Clip

Family

Companions

Bibliography

Notes

"I try to make films because I know that I have some sort of vision or insight . . . When I make a film I try to articulate it." For him, "it's the fire" of belief and commitment that makes the film, and goes on: "When I look back at my films I think they all came out of some sort of pain . . . I make films to rid myself of them, like ridding myself of a nightmare." It is not that he wants to "make confessions," only that for him film is "something which has more importance than my private life." --Werner Herzog, quoted in "World Film Directors", Volume Two, edited by John Wakeman