After learning how to craft film comedy from Fatty Arbuckle as the big man's sidekick in a series of one-reelers, Buster Keaton launched his solo career in 1920 with One Week, a charming two-reeler that he also co-wrote and co-directed. Producer Joseph Schenck had given Keaton his own production unit, Buster Keaton Comedies, and One Week became the first of 19 shorts and several features that Keaton made for Schenck between 1920 and 1928. He enjoyed complete creative control on these films, while his reputation as Chaplin's only rival rests on this output.

In 1919, Keaton saw an industrial documentary titled Home Made, which became the inspiration for One Week. Produced by the Ford Motor Co., Home Made explained the concept of prefabricated homes, which buyers assembled themselves by following a set of instructions. Sears, Roebuck and Co. had begun selling prefab homes in 1908, with styles and sizes available for all tastes and budgets. By the 1920s, the prefab trend had reached a high point. One Week parodies Home Made, borrowing events from the plot and following the narrative structure that divides the action into days of the week marked by pages falling from a calendar. Over the next few years, Keaton continued to parody contemporary trends or fads in his films, as in Cops (1922) when he spoofed the controversial craze for goat-gland injections popularized by a quack doctor named John R. Brinkley, or in Sherlock, Jr. (1924), when he poked fun at detective stories, which were all the rage in the 1920s.

In One Week, Keaton plays the Groom to Sybil Seely's Bride. The couple receives as a wedding gift a prefabricated house, which is packed compactly in a wooden box along with the instructions. While Keaton is busy elsewhere, his new wife's jealous ex-beau changes the numbers on the pieces to the house. As a result, Keaton builds an asymmetrical house with doors that open into midair and walls that pivot like a seesaw. After surviving a ferocious storm, in which the lop-sided house spins around and around, Keaton is informed by a city official that his house has been built on the wrong lot. He and his wife attempt to move their unique abode across town, but the task proves more difficult than anticipated.

Unlike other silent comedians who worked out their screen personas by trial and error over a period of time, Keaton's comic character--an extension of his vaudeville act--was fully established by One Week. Keaton's screen persona was dubbed the Great Stone Face, because of his ability to survive the most difficult and outrageous misfortunes without registering emotion. During the course of a film, his face reveals only the subtlest of expressions as he assesses his bad luck or twists of fate, then adapts to the situation with ingenuity and energy. To this day, viewers can identify with Keaton, because we have all fallen victim to the pitfalls of life, but the character never asks for pity or solicits sympathy. Instead his ingenuity invokes our admiration.

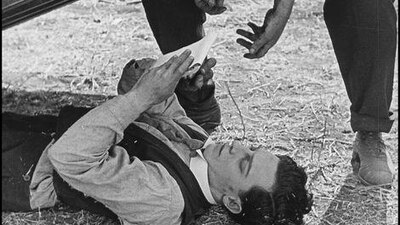

One Week also features many of the characteristics that define Keaton's style and reflect his interests. His comedies are renowned for his large-scale stunts and physical gags that show off his years of experience on the vaudeville stage in acrobatic comedy. Keaton could climb, take a pratfall, jump on and off moving vehicles, and handle large props with breathtaking skill and graceful ease. In the opening sequence of One Week, the Groom and Bride are being driven away from the wedding when they become dissatisfied with their nosey driver. Another car drives up along side them, and the couple proceeds to move from one vehicle to the other. The Bride successfully completes the maneuver, but Keaton gets stuck between the two cars when one drifts toward the edge of the road. He straddles the two vehicles with his legs spread widely apart, balancing as the cars weave a bit in the road. A motorcycle drives between his legs, and Keaton drops onto the handle bars as he and the biker race away. Further down the road, the motorcycle wipes out, with Keaton and the biker hurled into the dusty street. Known as a trajectory gag, this bit of physical comedy consists of several impressive stunts in a row propelled forward by a cause-and-effect logic that concludes with a big finish.

Sometimes these gags were made more astounding and therefore funnier through comic misdirection. Audiences anticipated certain outcomes based on the set up of the scene, but Keaton sometimes took the gag in a completely different direction. While the Groom stands astride two moving cars, viewers expect him to tumble onto the road or be dragged along by his legs; instead, a completely different type of vehicle comes along and inadvertently "rescues" him by scooping him up. Keaton eventually does fall but not in the way that was expected.

In the sequence in which Keaton is incorrectly putting together the pieces of his prefab home, an entire side of the house suddenly falls to the ground, with the hapless Groom seemingly about to be crushed. But, because he is standing right in the middle of the opening for the window, the wall falls down around him, and he walks away unscathed. The scale of his physical gags dictated that Keaton had to pull his camera back in order to capture the action, so a characteristic of his visual style is a predominance of long takes in long shots.

Keaton reworked some of his more remarkable gags for later films, making them more complex and improving on the way they were shot. The stunt with the two cars and the motorcycle in which Keaton lands on the cycle's handlebars was altered and expanded for Sherlock, Jr., while the stunt with the house falling around him as he is saved by a strategically placed window frame was re-imagined for Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928).

Along with stunts, Keaton's comedy featured gadgets and contraptions that revealed the comedian's own love of mechanical technology. Keaton could invent a whole series of jokes around a moving vehicle and rig doors, windows, and structures to spin, turn, and tilt on cue. Machines, gears, and tools were essential to his characters, who could jerry-rig, construct, and re-assemble anything to get out of a jam. In One Week, the build-it-yourself house serves as a giant contraption that the Groom finally gets together despite its lop-sided walls and doors that lead nowhere. For the storm sequence, Keaton attached the entire house to a giant turntable, so that the structure could rapidly spin, like a top on its axis.

In addition to exhibiting a command of filmmaking techniques, Keaton had a sophisticated awareness of the properties of cinema as a medium of expression. Some of his well-known films are famous for their self-reflexive gags--that is, jokes based on the nature and technology of cinema. Sherlock, Jr., about a projectionist who falls asleep and dreams himself to be the protagonist of a movie, is most often discussed as an example of this characteristic. However, as early as One Week, Keaton exhibited a talent for self-reflexive humor. In one scene, the Bride is taking a relaxing bath in the privacy of her new home when she drops the soap, which bounces across the floor. As she starts to step out of the tub, she gives a concerned look to the camera, which is suddenly covered by a large hand. The joke underscores the voyeuristic nature of cinema as it reminds the audience of the omnipresent camera.

In addition to exhibiting the characteristics of Keaton's films, One Week also established his informal working methods. Each film he made for Schenck began with the comedian, his co-director, the gagmen, and the other crew members hashing out the storyline and discussing how the gags would be worked into it. All crew members, from the prop men to the cinematographer, attended these meetings. After the basic plotline and the gag logistics were worked out, Keaton began shooting. He rarely worked with a formal script, because he didn't want every detail of his actors' performances to be rehearsed in advance. He wanted his stunts, gags, and character interactions to look fresh and spontaneous, not over-rehearsed. Sometimes, he improvised during a scene, particularly if a joke went wrong. He instructed his cameramen to always keep rolling if something didn't go as planned, because he claimed that his best improvisations occurred during those times.

Buster Keaton supervised every phase of filmmaking on his comedies for Schenck. However, his name is credited as co-director alongside those of Eddie Cline (Keaton's partner on One Week), Malcolm St. Clair, or Clyde Bruckman. The exact nature of the contributions of these men remains debated, but, given Keaton's creative control over his comic persona and his stunts, it is most likely that they served as assistant directors and gagmen more than co-directors.

One Week, an astonishing first effort for a novice filmmaker, established Keaton's working methods, solidified his onscreen comic persona, and prefigured his future films in style and structure.

Producer: Joseph M. Schenck (as presenter)

Directors: Edward F. Cline and Buster Keaton

Screenplay: Edward F. Cline and Buster Keaton

Cinematography: Elgin Lessley

Editor: Buster Keaton

Cast: The Groom (Buster Keaton), The Bride (Sybil Seely), Piano Mover (Joe Roberts).

BW-19m.

by Susan Doll

One Week

Brief Synopsis

Newlyweds receive a gift of a portable house that can be put together in one week.

Cast & Crew

Read More

Edward F. Cline

Director

Buster Keaton

Sybil Seely

Joe Roberts

Edward F. Cline

Writer (Uncredited)

Fred Gabourie

Technical Director

Film Details

Genre

Silent

Comedy

Short

Release Date

1920

Production Company

Joseph M. Schenck Productions

Distribution Company

Metro Pictures Corporation

Technical Specs

Duration

25m

Synopsis

Newlyweds receive a gift of a portable house that can be put together in one week.

Film Details

Genre

Silent

Comedy

Short

Release Date

1920

Production Company

Joseph M. Schenck Productions

Distribution Company

Metro Pictures Corporation

Technical Specs

Duration

25m

Articles

One Week

One Week

After learning how to craft film comedy from Fatty Arbuckle as the big man's sidekick in a series of one-reelers, Buster Keaton launched his solo career in 1920 with One Week, a charming two-reeler that he also co-wrote and co-directed. Producer Joseph Schenck had given Keaton his own production unit, Buster Keaton Comedies, and One Week became the first of 19 shorts and several features that Keaton made for Schenck between 1920 and 1928. He enjoyed complete creative control on these films, while his reputation as Chaplin's only rival rests on this output.

In 1919, Keaton saw an industrial documentary titled Home Made, which became the inspiration for One Week. Produced by the Ford Motor Co., Home Made explained the concept of prefabricated homes, which buyers assembled themselves by following a set of instructions. Sears, Roebuck and Co. had begun selling prefab homes in 1908, with styles and sizes available for all tastes and budgets. By the 1920s, the prefab trend had reached a high point. One Week parodies Home Made, borrowing events from the plot and following the narrative structure that divides the action into days of the week marked by pages falling from a calendar. Over the next few years, Keaton continued to parody contemporary trends or fads in his films, as in Cops (1922) when he spoofed the controversial craze for goat-gland injections popularized by a quack doctor named John R. Brinkley, or in Sherlock, Jr. (1924), when he poked fun at detective stories, which were all the rage in the 1920s.

In One Week, Keaton plays the Groom to Sybil Seely's Bride. The couple receives as a wedding gift a prefabricated house, which is packed compactly in a wooden box along with the instructions. While Keaton is busy elsewhere, his new wife's jealous ex-beau changes the numbers on the pieces to the house. As a result, Keaton builds an asymmetrical house with doors that open into midair and walls that pivot like a seesaw. After surviving a ferocious storm, in which the lop-sided house spins around and around, Keaton is informed by a city official that his house has been built on the wrong lot. He and his wife attempt to move their unique abode across town, but the task proves more difficult than anticipated.

Unlike other silent comedians who worked out their screen personas by trial and error over a period of time, Keaton's comic character--an extension of his vaudeville act--was fully established by One Week. Keaton's screen persona was dubbed the Great Stone Face, because of his ability to survive the most difficult and outrageous misfortunes without registering emotion. During the course of a film, his face reveals only the subtlest of expressions as he assesses his bad luck or twists of fate, then adapts to the situation with ingenuity and energy. To this day, viewers can identify with Keaton, because we have all fallen victim to the pitfalls of life, but the character never asks for pity or solicits sympathy. Instead his ingenuity invokes our admiration.

One Week also features many of the characteristics that define Keaton's style and reflect his interests. His comedies are renowned for his large-scale stunts and physical gags that show off his years of experience on the vaudeville stage in acrobatic comedy. Keaton could climb, take a pratfall, jump on and off moving vehicles, and handle large props with breathtaking skill and graceful ease. In the opening sequence of One Week, the Groom and Bride are being driven away from the wedding when they become dissatisfied with their nosey driver. Another car drives up along side them, and the couple proceeds to move from one vehicle to the other. The Bride successfully completes the maneuver, but Keaton gets stuck between the two cars when one drifts toward the edge of the road. He straddles the two vehicles with his legs spread widely apart, balancing as the cars weave a bit in the road. A motorcycle drives between his legs, and Keaton drops onto the handle bars as he and the biker race away. Further down the road, the motorcycle wipes out, with Keaton and the biker hurled into the dusty street. Known as a trajectory gag, this bit of physical comedy consists of several impressive stunts in a row propelled forward by a cause-and-effect logic that concludes with a big finish.

Sometimes these gags were made more astounding and therefore funnier through comic misdirection. Audiences anticipated certain outcomes based on the set up of the scene, but Keaton sometimes took the gag in a completely different direction. While the Groom stands astride two moving cars, viewers expect him to tumble onto the road or be dragged along by his legs; instead, a completely different type of vehicle comes along and inadvertently "rescues" him by scooping him up. Keaton eventually does fall but not in the way that was expected.

In the sequence in which Keaton is incorrectly putting together the pieces of his prefab home, an entire side of the house suddenly falls to the ground, with the hapless Groom seemingly about to be crushed. But, because he is standing right in the middle of the opening for the window, the wall falls down around him, and he walks away unscathed. The scale of his physical gags dictated that Keaton had to pull his camera back in order to capture the action, so a characteristic of his visual style is a predominance of long takes in long shots.

Keaton reworked some of his more remarkable gags for later films, making them more complex and improving on the way they were shot. The stunt with the two cars and the motorcycle in which Keaton lands on the cycle's handlebars was altered and expanded for Sherlock, Jr., while the stunt with the house falling around him as he is saved by a strategically placed window frame was re-imagined for Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928).

Along with stunts, Keaton's comedy featured gadgets and contraptions that revealed the comedian's own love of mechanical technology. Keaton could invent a whole series of jokes around a moving vehicle and rig doors, windows, and structures to spin, turn, and tilt on cue. Machines, gears, and tools were essential to his characters, who could jerry-rig, construct, and re-assemble anything to get out of a jam. In One Week, the build-it-yourself house serves as a giant contraption that the Groom finally gets together despite its lop-sided walls and doors that lead nowhere. For the storm sequence, Keaton attached the entire house to a giant turntable, so that the structure could rapidly spin, like a top on its axis.

In addition to exhibiting a command of filmmaking techniques, Keaton had a sophisticated awareness of the properties of cinema as a medium of expression. Some of his well-known films are famous for their self-reflexive gags--that is, jokes based on the nature and technology of cinema. Sherlock, Jr., about a projectionist who falls asleep and dreams himself to be the protagonist of a movie, is most often discussed as an example of this characteristic. However, as early as One Week, Keaton exhibited a talent for self-reflexive humor. In one scene, the Bride is taking a relaxing bath in the privacy of her new home when she drops the soap, which bounces across the floor. As she starts to step out of the tub, she gives a concerned look to the camera, which is suddenly covered by a large hand. The joke underscores the voyeuristic nature of cinema as it reminds the audience of the omnipresent camera.

In addition to exhibiting the characteristics of Keaton's films, One Week also established his informal working methods. Each film he made for Schenck began with the comedian, his co-director, the gagmen, and the other crew members hashing out the storyline and discussing how the gags would be worked into it. All crew members, from the prop men to the cinematographer, attended these meetings. After the basic plotline and the gag logistics were worked out, Keaton began shooting. He rarely worked with a formal script, because he didn't want every detail of his actors' performances to be rehearsed in advance. He wanted his stunts, gags, and character interactions to look fresh and spontaneous, not over-rehearsed. Sometimes, he improvised during a scene, particularly if a joke went wrong. He instructed his cameramen to always keep rolling if something didn't go as planned, because he claimed that his best improvisations occurred during those times.

Buster Keaton supervised every phase of filmmaking on his comedies for Schenck. However, his name is credited as co-director alongside those of Eddie Cline (Keaton's partner on One Week), Malcolm St. Clair, or Clyde Bruckman. The exact nature of the contributions of these men remains debated, but, given Keaton's creative control over his comic persona and his stunts, it is most likely that they served as assistant directors and gagmen more than co-directors.

One Week, an astonishing first effort for a novice filmmaker, established Keaton's working methods, solidified his onscreen comic persona, and prefigured his future films in style and structure.

Producer: Joseph M. Schenck (as presenter)

Directors: Edward F. Cline and Buster Keaton

Screenplay: Edward F. Cline and Buster Keaton

Cinematography: Elgin Lessley

Editor: Buster Keaton

Cast: The Groom (Buster Keaton), The Bride (Sybil Seely), Piano Mover (Joe Roberts).

BW-19m.

by Susan Doll

Buster Keaton: The Short Films Collection, 1920-1923 - A New Release from Kino

We're accustomed to seeing Buster Keaton's early short films piecemeal, as a

special treat on a screening schedule or as an extra for a silent comedy feature.

Kino's Buster Keaton The Short Films Collection collects all nineteen of

the independent two-reelers Keaton made between 1920 and 1923. Assembled in one

group, the films show the screen comedian refining his solo persona and developing

a style more dependent on realism than cartoonish gags.

Coming directly from a productive apprenticeship with Fatty Arbuckle, Keaton was already adept with standard comedy material -- his pratfalls were the wildest on screen and no physical gag seemed too impossible for him. The Arbuckle-Keaton silent comedies are some of the funniest ever; we only wish that more of them existed in better-quality prints. Backer Joseph Schenck helped Buster move into Charles Chaplin's old Hollywood studio near the corner of Santa Monica Blvd. and Vine Street, where he began filming almost immediately.

Keaton's nineteen shorts include oft-screened favorites and others not nearly as well known. The High Sign was filmed first but held up for a year because Keaton thought it was too much like an Arbuckle production. An extortion gang hires Buster to assassinate a businessman, who immediately hires Buster as a bodyguard. A bravura chase threads through a house rigged with a number of trap doors and secret passageways, the kind of technical challenge that appealed to Keaton and his head engineer- gag-builder, Fred Gabourie.

Now recognized as his first solo masterpiece, Keaton's One Week takes silent comedy in a new direction. Its dry wit and physical logic immediately distinguish it from the frantic two-reelers by other comedians of 1920. Calendar pages count off the days as newlyweds cheerfully build a prefabricated house, not realizing that the assembly instructions have been sabotaged. The proud homeowners remain calm as the uninhabitable structure turns into a surreal nightmare. Keaton "tops" each crazy gag with one even more absurd, until the house meets its fate on some railroad tracks.

One Week is core Keaton in that none of its jokes are blatantly impossible. When things go "crazy" in his filmic universe, the physicality of what occurs remains stubbornly logical: Buster is never hammered into the ground or chopped into pieces. Keaton disliked cartoonish gags, such as a bit in The High Sign where he hangs his jacket on a hook that he's drawn on the wall with chalk. His is a more honest struggle with the modern world. When Laurel & Hardy are mangled by shop tools or crushed by runaway pianos, we sometimes want the torture to stop. Keaton's energetic hero understands little of the forces that are ruining his plans, but he never howls or complains.

The endless pursuit of Buster by an army of Cops therefore takes on an abstract quality. We laugh at individual stunts and marvel at the masses of uniforms that Buster seemingly cannot escape. Surrealists loved Keaton's innocent clashes with authority, and taken as a whole his films do make a whimsical artistic statement about the Human Condition. Many a Keaton hero ends up jailed or destitute, his boat sunk or his house destroyed, without ever really understanding what has happened.

Some of Keaton's humor is downright sadistic. Convict 13 has plenty of black comedy, with guards and inmates shot and clubbed by the score; Buster stages several gags on a grim execution scaffold. Other short subjects are organized around interesting design ideas. Symmetrical backyards separated by a fence keep young lovers apart in Neighbors, but Buster visits his girl by climbing across second-story clotheslines. Buster's gags often involve visual illusions. In one film the bars of an iron gate fool us into thinking that he's in prison. In another, a spare tire that Buster hops on to hitch a ride turns out to be a display sitting on the ground, and not attached to the automobile. Keaton sets up his story with silent inter-titles but normally avoids verbal jokes. A telling exception is a gag in which a man wanders into a party covered in bandages. Another guest asks, "What happened to you?" He answers: "I bought a Ford."

Keaton and his team loved elaborate mechanical gags. Functioning inventions adorn The Electric House, including a device that racks billiard balls. The Boat is practically a dry run for the director's later feature classic The Navigator. The voyage of the good ship Damfino is one disaster after another, even when Keaton's little dinghy remains tied up to the dock. The Playhouse is Keaton at his most surreal. Multiple exposures populate an entire musical theater -- actors, audience, musicians -- with duplicates of Buster Keaton. Several Keatons playing musical instruments interact perfectly; no mattes are visible. Technically, Keaton is forty years ahead of his time.

In 1923 Schenck and the backers insisted that Keaton abandon short subjects and move up to the more profitable arena of feature film production. As we've already seen, his first feature effort Three Ages was organized to be easily split into three separate short subjects, should he prove unpopular in the longer format.

Kino International's Blu-ray of Buster Keaton The Short Films Collection 1920-1923 is an archival-quality assembly. Only a couple of these 90 year-old gems are in perfect condition but all are presented at the best level of restoration so far attained. Once thought to be lost, the final short The Love Nest appears here in a reasonably good print. Day Dreams is missing several flashbacks, perhaps because they were printed on tinted film stock that deteriorated while the rest of the film remained intact. A couple of the shorts exist only in quality much poorer than the norm, and are included for the sake of completeness. The set comes on three separate Blu-ray discs, in order of filming. Each comedy has a newly recorded musical accompaniment.

As is their policy, Kino has not used digital enhancement, as that process invariably softens the image as it minimizes visual flaws. But as an extra feature, five of the shorts (The High Sign, The Balloonatic, The Boat and Cops) have been run through digital processing. Curious viewers can compare the results for themselves.

The ample extras provide a wealth of background information about this formative chapter in Keaton's career. Visual essays analyze fifteen titles, and are authored by experts including Bruce Lawton, David Kalat and Bret Wood. Keaton biographer Jeffrey Vance contributes an essay to the disc set's insert booklet. Locations expert John Bengtson details local sites where Keaton filmed. Vintage photos reveal most of Los Angeles in 1922 as empty acreage crisscrossed by dirt roads. A three-block strip of Cahuenga Blvd. saw a lot of Keaton production activity, as did a warren of downtown alleyways later wiped out by the Hollywood Freeway. Other menu choices lead viewers to alternate and deleted scenes, with a generous helping of related films by other silent comedians.

For more information about Buster Keaton The Short Films Collection 1920-1923, visit Kino Lorber. To order Buster Keaton The Short Films Collection 1920-1923, go to TCM Shopping.

by Glenn Erickson

Coming directly from a productive apprenticeship with Fatty Arbuckle, Keaton was already adept with standard comedy material -- his pratfalls were the wildest on screen and no physical gag seemed too impossible for him. The Arbuckle-Keaton silent comedies are some of the funniest ever; we only wish that more of them existed in better-quality prints. Backer Joseph Schenck helped Buster move into Charles Chaplin's old Hollywood studio near the corner of Santa Monica Blvd. and Vine Street, where he began filming almost immediately.

Keaton's nineteen shorts include oft-screened favorites and others not nearly as well known. The High Sign was filmed first but held up for a year because Keaton thought it was too much like an Arbuckle production. An extortion gang hires Buster to assassinate a businessman, who immediately hires Buster as a bodyguard. A bravura chase threads through a house rigged with a number of trap doors and secret passageways, the kind of technical challenge that appealed to Keaton and his head engineer- gag-builder, Fred Gabourie.

Now recognized as his first solo masterpiece, Keaton's One Week takes silent comedy in a new direction. Its dry wit and physical logic immediately distinguish it from the frantic two-reelers by other comedians of 1920. Calendar pages count off the days as newlyweds cheerfully build a prefabricated house, not realizing that the assembly instructions have been sabotaged. The proud homeowners remain calm as the uninhabitable structure turns into a surreal nightmare. Keaton "tops" each crazy gag with one even more absurd, until the house meets its fate on some railroad tracks.

One Week is core Keaton in that none of its jokes are blatantly impossible. When things go "crazy" in his filmic universe, the physicality of what occurs remains stubbornly logical: Buster is never hammered into the ground or chopped into pieces. Keaton disliked cartoonish gags, such as a bit in The High Sign where he hangs his jacket on a hook that he's drawn on the wall with chalk. His is a more honest struggle with the modern world. When Laurel & Hardy are mangled by shop tools or crushed by runaway pianos, we sometimes want the torture to stop. Keaton's energetic hero understands little of the forces that are ruining his plans, but he never howls or complains.

The endless pursuit of Buster by an army of Cops therefore takes on an abstract quality. We laugh at individual stunts and marvel at the masses of uniforms that Buster seemingly cannot escape. Surrealists loved Keaton's innocent clashes with authority, and taken as a whole his films do make a whimsical artistic statement about the Human Condition. Many a Keaton hero ends up jailed or destitute, his boat sunk or his house destroyed, without ever really understanding what has happened.

Some of Keaton's humor is downright sadistic. Convict 13 has plenty of black comedy, with guards and inmates shot and clubbed by the score; Buster stages several gags on a grim execution scaffold. Other short subjects are organized around interesting design ideas. Symmetrical backyards separated by a fence keep young lovers apart in Neighbors, but Buster visits his girl by climbing across second-story clotheslines. Buster's gags often involve visual illusions. In one film the bars of an iron gate fool us into thinking that he's in prison. In another, a spare tire that Buster hops on to hitch a ride turns out to be a display sitting on the ground, and not attached to the automobile. Keaton sets up his story with silent inter-titles but normally avoids verbal jokes. A telling exception is a gag in which a man wanders into a party covered in bandages. Another guest asks, "What happened to you?" He answers: "I bought a Ford."

Keaton and his team loved elaborate mechanical gags. Functioning inventions adorn The Electric House, including a device that racks billiard balls. The Boat is practically a dry run for the director's later feature classic The Navigator. The voyage of the good ship Damfino is one disaster after another, even when Keaton's little dinghy remains tied up to the dock. The Playhouse is Keaton at his most surreal. Multiple exposures populate an entire musical theater -- actors, audience, musicians -- with duplicates of Buster Keaton. Several Keatons playing musical instruments interact perfectly; no mattes are visible. Technically, Keaton is forty years ahead of his time.

In 1923 Schenck and the backers insisted that Keaton abandon short subjects and move up to the more profitable arena of feature film production. As we've already seen, his first feature effort Three Ages was organized to be easily split into three separate short subjects, should he prove unpopular in the longer format.

Kino International's Blu-ray of Buster Keaton The Short Films Collection 1920-1923 is an archival-quality assembly. Only a couple of these 90 year-old gems are in perfect condition but all are presented at the best level of restoration so far attained. Once thought to be lost, the final short The Love Nest appears here in a reasonably good print. Day Dreams is missing several flashbacks, perhaps because they were printed on tinted film stock that deteriorated while the rest of the film remained intact. A couple of the shorts exist only in quality much poorer than the norm, and are included for the sake of completeness. The set comes on three separate Blu-ray discs, in order of filming. Each comedy has a newly recorded musical accompaniment.

As is their policy, Kino has not used digital enhancement, as that process invariably softens the image as it minimizes visual flaws. But as an extra feature, five of the shorts (The High Sign, The Balloonatic, The Boat and Cops) have been run through digital processing. Curious viewers can compare the results for themselves.

The ample extras provide a wealth of background information about this formative chapter in Keaton's career. Visual essays analyze fifteen titles, and are authored by experts including Bruce Lawton, David Kalat and Bret Wood. Keaton biographer Jeffrey Vance contributes an essay to the disc set's insert booklet. Locations expert John Bengtson details local sites where Keaton filmed. Vintage photos reveal most of Los Angeles in 1922 as empty acreage crisscrossed by dirt roads. A three-block strip of Cahuenga Blvd. saw a lot of Keaton production activity, as did a warren of downtown alleyways later wiped out by the Hollywood Freeway. Other menu choices lead viewers to alternate and deleted scenes, with a generous helping of related films by other silent comedians.

For more information about Buster Keaton The Short Films Collection 1920-1923, visit Kino Lorber. To order Buster Keaton The Short Films Collection 1920-1923, go to TCM Shopping.

by Glenn Erickson

Buster Keaton: The Short Films Collection, 1920-1923 - A New Release from Kino

We're accustomed to seeing Buster Keaton's early short films piecemeal, as a

special treat on a screening schedule or as an extra for a silent comedy feature.

Kino's Buster Keaton The Short Films Collection collects all nineteen of

the independent two-reelers Keaton made between 1920 and 1923. Assembled in one

group, the films show the screen comedian refining his solo persona and developing

a style more dependent on realism than cartoonish gags.

Coming directly from a productive apprenticeship with Fatty Arbuckle, Keaton was

already adept with standard comedy material -- his pratfalls were the wildest on

screen and no physical gag seemed too impossible for him. The Arbuckle-Keaton

silent comedies are some of the funniest ever; we only wish that more of them

existed in better-quality prints. Backer Joseph Schenck helped Buster move into

Charles Chaplin's old Hollywood studio near the corner of Santa Monica Blvd. and

Vine Street, where he began filming almost immediately.

Keaton's nineteen shorts include oft-screened favorites and others not nearly as

well known. The High Sign was filmed first but held up for a year because

Keaton thought it was too much like an Arbuckle production. An extortion gang

hires Buster to assassinate a businessman, who immediately hires Buster as a

bodyguard. A bravura chase threads through a house rigged with a number of trap

doors and secret passageways, the kind of technical challenge that appealed to

Keaton and his head engineer- gag-builder, Fred Gabourie.

Now recognized as his first solo masterpiece, Keaton's One Week takes

silent comedy in a new direction. Its dry wit and physical logic immediately

distinguish it from the frantic two-reelers by other comedians of 1920. Calendar

pages count off the days as newlyweds cheerfully build a prefabricated house, not

realizing that the assembly instructions have been sabotaged. The proud homeowners

remain calm as the uninhabitable structure turns into a surreal nightmare. Keaton

"tops" each crazy gag with one even more absurd, until the house meets its fate on

some railroad tracks.

One Week is core Keaton in that none of its jokes are blatantly impossible.

When things go "crazy" in his filmic universe, the physicality of what occurs

remains stubbornly logical: Buster is never hammered into the ground or chopped

into pieces. Keaton disliked cartoonish gags, such as a bit in The High

Sign where he hangs his jacket on a hook that he's drawn on the wall with

chalk. His is a more honest struggle with the modern world. When Laurel & Hardy

are mangled by shop tools or crushed by runaway pianos, we sometimes want the

torture to stop. Keaton's energetic hero understands little of the forces that are

ruining his plans, but he never howls or complains.

The endless pursuit of Buster by an army of Cops therefore takes on an

abstract quality. We laugh at individual stunts and marvel at the masses of

uniforms that Buster seemingly cannot escape. Surrealists loved Keaton's innocent

clashes with authority, and taken as a whole his films do make a whimsical

artistic statement about the Human Condition. Many a Keaton hero ends up jailed or

destitute, his boat sunk or his house destroyed, without ever really understanding

what has happened.

Some of Keaton's humor is downright sadistic. Convict 13 has plenty of

black comedy, with guards and inmates shot and clubbed by the score; Buster stages

several gags on a grim execution scaffold. Other short subjects are organized

around interesting design ideas. Symmetrical backyards separated by a fence keep

young lovers apart in Neighbors, but Buster visits his girl by climbing

across second-story clotheslines. Buster's gags often involve visual illusions. In

one film the bars of an iron gate fool us into thinking that he's in prison. In

another, a spare tire that Buster hops on to hitch a ride turns out to be a

display sitting on the ground, and not attached to the automobile. Keaton sets up

his story with silent inter-titles but normally avoids verbal jokes. A telling

exception is a gag in which a man wanders into a party covered in bandages.

Another guest asks, "What happened to you?" He answers: "I bought a Ford."

Keaton and his team loved elaborate mechanical gags. Functioning inventions adorn

The Electric House, including a device that racks billiard balls. The

Boat is practically a dry run for the director's later feature classic The

Navigator. The voyage of the good ship Damfino is one disaster after another,

even when Keaton's little dinghy remains tied up to the dock. The Playhouse

is Keaton at his most surreal. Multiple exposures populate an entire musical

theater -- actors, audience, musicians -- with duplicates of Buster Keaton.

Several Keatons playing musical instruments interact perfectly; no mattes are

visible. Technically, Keaton is forty years ahead of his time.

In 1923 Schenck and the backers insisted that Keaton abandon short subjects and

move up to the more profitable arena of feature film production. As we've already

seen, his first feature effort Three Ages was

organized to be easily split into three separate short subjects, should he prove

unpopular in the longer format.

Kino International's Blu-ray of Buster Keaton The Short Films Collection

1920-1923 is an archival-quality assembly. Only a couple of these 90 year-old

gems are in perfect condition but all are presented at the best level of

restoration so far attained. Once thought to be lost, the final short The Love

Nest appears here in a reasonably good print. Day Dreams is missing

several flashbacks, perhaps because they were printed on tinted film stock that

deteriorated while the rest of the film remained intact. A couple of the shorts

exist only in quality much poorer than the norm, and are included for the sake of

completeness. The set comes on three separate Blu-ray discs, in order of filming.

Each comedy has a newly recorded musical accompaniment.

As is their policy, Kino has not used digital enhancement, as that process

invariably softens the image as it minimizes visual flaws. But as an extra

feature, five of the shorts (The High Sign, The Balloonatic, The Boat and

Cops) have been run through digital processing. Curious viewers can compare

the results for themselves.

The ample extras provide a wealth of background information about this formative

chapter in Keaton's career. Visual essays analyze fifteen titles, and are authored

by experts including Bruce Lawton, David Kalat and Bret Wood. Keaton biographer

Jeffrey Vance contributes an essay to the disc set's insert booklet. Locations

expert John Bengtson details local sites where Keaton filmed. Vintage photos

reveal most of Los Angeles in 1922 as empty acreage crisscrossed by dirt roads. A

three-block strip of Cahuenga Blvd. saw a lot of Keaton production activity, as

did a warren of downtown alleyways later wiped out by the Hollywood Freeway. Other

menu choices lead viewers to alternate and deleted scenes, with a generous helping

of related films by other silent comedians.

For more information about Buster Keaton The Short Films Collection

1920-1923, visit Kino Lorber. To order Buster Keaton The Short

Films Collection 1920-1923, go to

TCM Shopping.

by Glenn Erickson