L'Atalante

Brief Synopsis

Cast & Crew

Jean Vigo

Michel Simon

Dita Parlo

Jean Dasté

Gilles Margaritis

Louis Lefebvre

Film Details

Technical Specs

Synopsis

When Juliette marries Jean, she comes to live on his ship with a cabin boy and a strange old second mate named Pere Jules. Soon bored by river life, she is instantly drawn to the Paris nightlife. Angered by this, Jean sets off, leaving Juliette behind and falling into a deep depression.

Director

Jean Vigo

Cast

Michel Simon

Dita Parlo

Jean Dasté

Gilles Margaritis

Louis Lefebvre

Fanny Clar

Maurice Gilles

Rafa Diligent

Claude Aveline

Rene Blech

Paul Grimault

Genya Lozinska

Gen Paul

Jacques Prevert

Pierre Prevert

Albert Riera

Lou Tchimoukoff

Crew

Jean-paul Alphen

Henri Arbel

Lucien Baujard

Louis Berger

Cesare Andrea Bixio

Jean-louis Bompoint

Acho Chakatouny

Louis Chavance

Charles Goldblatt

Charles Goldblatt

Jean Guinee

Jean Guinee

Maurice Jaubert

Maurice Jaubert

Maurice Jaubert

Francis Jourdain

Boris Kaufman

Fred Matter

Pierre Merle

Jacqueline Morland

Jacques Louis Nounez

Roger Parry

Pierre Philippe

Albert Riera

Albert Riera

Albert Riera

Marcel Royne

Jean Vigo

Jean Vigo

Videos

Movie Clip

Film Details

Technical Specs

Articles

L'Atalante

And yet for all its primal urgency and the rough textures of its everyday working world, Vigo's film was meticulously assembled. The spell it casts begins with an almost crude simplicity, a wedding procession walking at a fast clip from an old village church to a nearby riverbank and a barge, the name of which gives the film its title, moored alongside it. The groom, wearing a visored cap, immediately changes from his suit to the rest of his work clothes. After perfunctory goodbyes to the wedding gathered onshore, the captain (Jean Daste), his bride (Dita Parlo), the engineer (Michel Simon) and the cabin boy (Louis Lefebvre) lose no time departing. The bride, smiling on her way from the church, now looks decontextualized, unmoored, a little lost, a little sad, as she walks the barge's long hatch cover in a wedding gown forlornly out of place.

Clearly she hasn't known her groom long. Clearly part of her reason for getting married was to escape her provincial setting. "Are you bored?" he asks, seeing that she obviously is. "I'll show you the world," he adds, placatingly. "River banks," she sighs, and their marriage festers. This is probably the place to say that Vigo avoids barge-tour lyricism. He was working-class poor, and concentrates on the claustrophobic barge life and the claustrophobic psychic space in which all co-exist, not the bucolic charms of the countryside through which they pass as they navigate canals, locks and rivers all the way to Le Havre by way of Paris. And yet Vigo, whose life was cut short at 29 by tuberculosis after completing this first feature and who died thinking he was a failure, has not become known as the father of French poetic realism for nothing.

The barge, which has a lot of mileage on it, and the take-the-camera-into-the-streets approach that caused the film to be dismissed as amateurish when it opened and later was admired and emulated by the New Wave filmmakers, may look realistic (interiors were shot at Gaumont's studios), but the film plays like a rapturous dream. Vigo is too keenly aware of loss to ever romanticize the world of his films, but when the young wife, Juliette, storms off to make more contact with the bright lights of Paris after hubby Jean whisks her away in a possessive rage when he thinks her too receptive to the glib charms of a peddler in a dance hall, his angry sulk gives way to a catatonic depression. He does seem a bit of a pill. Bereft, he jumps into the river, ready to end it all, until he sees a vision of her while underwater and changes his mind. It's the scene most often cited by admirers of the film.

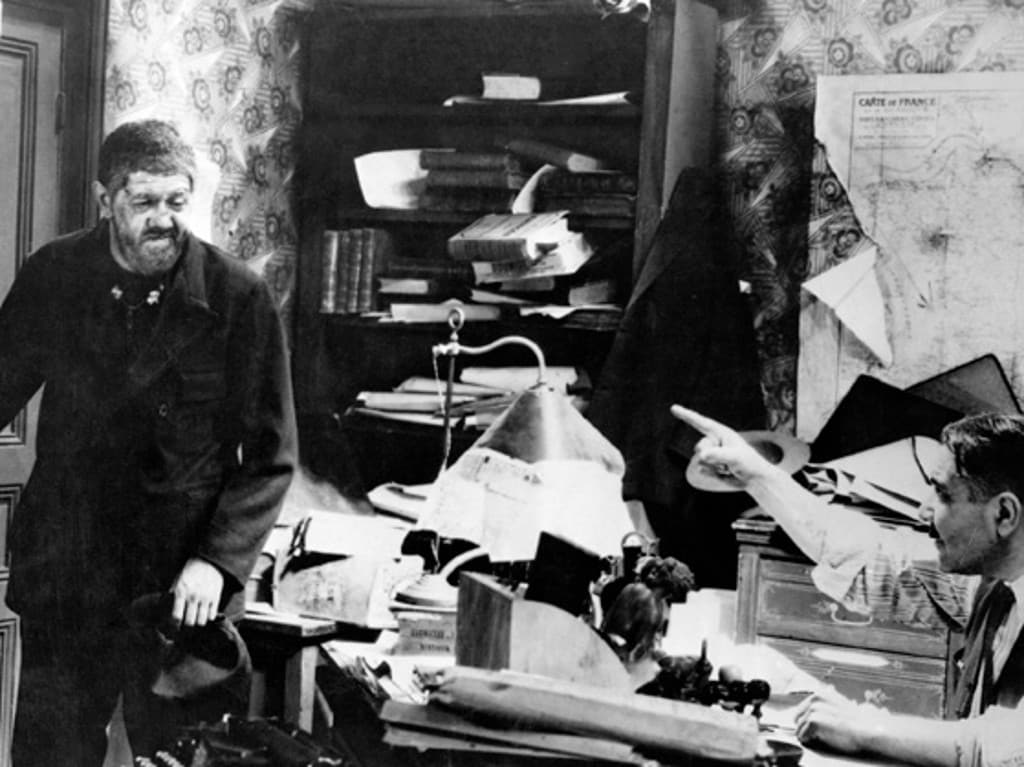

And yet the scene that seems the key to the film, and the heart of it, takes place in the cramped cabin of the gruff old engineer, Simon (the best role of a distinguished career and the actor's own personal favorite). You expect his living quarters to reflect the grizzled roughneck of a character who drinks too much. But far from being littered with empty bottles and cigarette packs, the place is an enchanted cave, filled with exotic objects, souvenirs of his globe-circling life, many pictures of women, numerous mechanical objects, including figurines, some of which he has restored to working order, some of which he hasn't got around to. It's clear that he's not just inviting her into his cabin; he's inviting her into his psychic space. Far more resonantly surrealistic than the oft-cited underwater scene is this one in which he shows Juliette his assemblage of mementos.

None are in themselves valuable, but they're surrealistically juxtaposed. In their arbitrary, capricious nature and apparent disorder, they amount to a rejection of the bourgeois world - much like the Dadaist and surrealist art of the era. Simon borrowed a lot of the coarseness of this film's Jules from the title role of Jean Renoir's Boudu Saved from Drowning (1932), which made him a star in the role of a contentedly homeless ne'er-do-well and gave rise to the Al Jolson vehicle, Hallelujah, I'm a Bum (1933). Simon's Jules is just as much an anarchic force as Boudu, totally uninterested in integrating into bourgeois society. He reminds us that while much has been written about Vigo the lyric poet enthralled by dreams and surrealism like many artists of his time, Vigo was in real life the child of a father who died in prison for his anarchic beliefs. His first short film, A propos de Nice (1930), subverted the travelogue. Once past the obligatory palm trees, promenades and joyless rich in casinos, he couldn't wait to cut to the working classes who lived in Nice's back streets.

Although much in L'Atalante seems to have wafted up from Vigo's subconscious, it was in fact carefully planned. Vigo himself scoured flea markets and junkyards to get just the right blend of objects to embody Jules's cave of memories. Long before the end, there's no mistaking the reason Jules is referred to as Pere Jules. When Jean stops functioning, Jules steps in and saves his job. In the end, after Jean and Juliette have broken up and are reunited, thanks to Jules finding her while Jean sits and mopes, Jules emerges an archetypal father figure. Literally and figuratively, his charmed and charming Mr. Fixit lowers the lid on them (well, hatch cover) after they go below deck, together again. There's something transcendentally endearing about an anarchic figure, far from destroying his world, fixing it and bringing it back to life. L'Atalante is a spellbinding excursion, lulling you into its fluid, layered world.

Producer: Jacques-Louis Nounez

Director: Jean Vigo

Screenplay: Albert Riéra, Jean Vigo (adaptation and dialogue); Jean Guinée (scenario)

Cinematography: Louis Berger, Boris Kaufman; Jean-Paul Alphen (originally uncredited)

Art Direction: Francis Jourdain

Music: Maurice Jaubert

Film Editing: Louis Chavance

Cast: Michel Simon (Le père Jules), Dita Parlo (Juliette), Jean Dasté (Jean), Gilles Margaritis (Le camelot), Louis Lefebvre (Le gosse), Maurice Gilles (Le chef de bureau), Rafa Diligent (Raspoutine, le batelier)

BW-89m.

by Jay Carr

L'Atalante

The Complete Jean Vigo - THE COMPLETE JEAN VIGO - A Tribute to a Pivotal Film Artist from The Criterion Collection

Jean Vigo's anarchic style made a splash with his very first film. His first effort À propos de Nice is a silent docu-essay about the French resort town of Nice. It soon departs from the established agenda of the 'city symphony' experimental subgenre. Vigo's camera instead seems to X-ray the social and psychological aspects of life on the ritzy Nice beachfront, where the wealthy come to soak in the sun and display their affluence.

Without a narration or a soundtrack, comparisons of rich and poor take second position to surreal, often humorous visions. Shots of well-dressed folk on the beachfront walk are interrupted by a shot of an ostrich's head, looking just as self-satisfied; it's only the beginning of a number of wickedly satiric cutaways to animals and statuary. Workers wash the gutters and set out the tables, and then proceed to manicure the trees and sculpt garish costumes for the carnaval celebration. Shots of the boats, cars and airplanes of the rich are followed by a poor man's odd, custom-made bicycle apparatus. Vigo analyzes a chic woman of fashion sitting in a deck chair: her expensive clothes disappear layer by layer until she lounges in the nude, without ever changing her fashionably disinterested attitude. When the carnaval parade becomes a riot of movement and dancing, the 'giant head' sculpted costumes go on parade, like strange gods. Vigo's camera looks up the dresses of a group of revelers atop a platform. The girls kick their legs up, inviting our gaze. The display may be decadent but it rounds out the portrait of a town that dispenses pleasures to the well heeled.

À propos de Nice was a genuine Avant-garde attraction shown in film clubs and in a few art theaters; Jean Vigo was reportedly inspired by the classic of that circuit, Buñuel's An Andalusian Dog. His second film Taris is a nine-minute commission job to celebrate the skill of a French swimming champion. Vigo simply records the swimmer in slow motion, producing a respectable record of an athlete.

At this point producer Jacques-Louis Nounez stepped in and offered Vigo the opportunity to make a theatrical film to fit into a 'short feature' category. The director wrote the wildly surreal Zéro de conduite, a subversive comedy about rebellion in a boy's school. A timeless hymn to anti-authoritarian revolt, the show is a parade of absurdities. With the exception of one free spirit who does Charlie Chaplin impersonations, the teachers are neurotics, martinets or closeted perverts. One sneaks into empty classrooms to steal the boys' snacks and candy, while another makes obvious overtures to a boy deemed a sissy. The headmaster is a pompous midget with an enormous beard, who struggles to use normal-sized furniture. A group of incorrigibly mischievous students disobey the rules and laugh at their punishments, all the while plotting to disrupt a school celebration attended by local dignitaries -- represented by a line of uniformed boors, their seating gallery augmented by a row of stuffed dummies. The most famous scene is an anarchic pillow fight that ends in a slow-motion procession through a hail of feathers. The movie celebrates rebellion for its own sake.

The Zéro de conduite premiere was cheered and booed by a mixed audience of conservative press representatives and the artistic intelligentsia. The censors banned it outright, citing it as a potentially corrupting influence on society. French censors have traditionally been sensitive to criticism of established authority, and Vigo's Jeunes diables think nothing of addressing their superiors with unrepentant obscenities. A minor celebrity with an un-releasable film, Jean Vigo might have been forced to seek an artistic patron and retreat to short subjects. Instead, producer Nounez suggested that he try a less controversial subject. Vigo 'adjusted' an existing screenplay about a young married couple's first trip on their barge, from the bride's rural hometown to Paris. Rather than affect a satirical tone or attack the status quo with shocking images, Vigo fashioned his final film L'Atalante as a sensual, romantic dream.

The outwardly conventional L'Atalante begins when barge captain Jean (Jean Dasté) marries the inexperienced Juliette (Dita Parlo). She leaves her unhappy relatives behind, happy to see something beyond her village. As the barge cruises slowly through the misty countryside we share scenes of domestic bliss (Jean and Juliette prepare their marriage bed by shooing away a group of cats) and ethereal visuals (Juliette strides the length of the barge in her wedding dress, like a white ghost). Many sequences observe the odd behavior of La père Jules (Michel Simon), a crewmember with a huge, shapeless face and a collection of souvenirs gathered on his many voyages. Discord comes when Juliette and Jean's hoped-for nighttime excursion into Paris must be canceled, and things become worse when Juliette is charmed by a traveling salesman / entertainer (Gilles Margaritis), who serenades her with nonsense songs. The newlyweds fight, and Jean abandons Juliette when she goes ashore alone to think things out. With Jean soon collapsing into lovesick misery, even the optimistic Jules doesn't know if a happy ending is possible.

L'Atalante stays connected to the Avant-garde through its hazy, hallucinatory dream imagery. Juliette tells Jean that a reflection in water predicted their romance. The despondent Jean jumps overboard, and sees a vision of Juliette as an underwater spirit. In his delirium he walks to the sea, perhaps to kill himself. There follows a montage of dissolved shots of the couple sleeping alone but sharing an erotic loss of the other. The non-linear images express the attraction between lovers as something that transcends the physical.

Jean Vigo was never in good health, and is said to have literally worked himself to death making L'Atalante. Vigo's creative team, which included cinematographer Boris Kaufman (On the Waterfront, Twelve Angry Men) and composer Maurice Jaubert Drôle de drame, Le quai des brumes) were committed to his genius, and shocked when the distributor Gaumont radically re-edited L'Atalante and re-titled it with the name of a current song hit, Le chaland qui passe. Too sick to complete the editing, Vigo died only a few months later, convinced that his life's pursuit had been a failure. Of his two features one was unreleased and the other mangled beyond recognition. As detailed in an excellent documentary included on Criterion's disc, something close to his original cut was released under its proper title in 1940, at the beginning of the German Occupation. Jean Vigo's genius would be acknowledged after the war, when the Cinematheque crowd rediscovered À propos de Nice as well. Recent restorations have greatly improved both features, recovering footage and improving the visual quality. Jean Vigo is now more than ever regarded as one of the best directors in film history.

Criterion's Blu-ray of The Complete Jean Vigo will be an audiovisual feast to students and cinephiles that recall older, frequently inaudible 16mm prints. All four pictures exhibit wear and a variety of minor damage, but the clarity and sharpness of the restored HD images is sometimes startling. À propos de Nice looks remarkably good, and the print of Zéro de conduite allows us to enjoy oddball details, such as the teacher that maintains his Chaplin imitation right through the final "battle". We now can say with assurance that Lindsay Anderson's If.... is really a direct remake of Vigo's film.

All four films carry commentaries by Vigo biographer Michael Temple, and the music score for the silent À propos de Nice is by composer Marc Perrone.

Criterion has lucked into an ideal group of extras for their deluxe disc set, thanks to the French television's interest in all things cinematic. A 1964 overview of the life and films of Jean Vigo benefits from the participation of several of the filmmaker's collaborators and actors, all of which gladly recall their experiences. We learn the particulars of Vigo's upbringing: his father was an anarchist publisher murdered in prison for his pacifism in WW1. Had he lived, a truly marvelous career might have been the result.

In another excellent TV excerpt, Eric Rohmer interviews François Truffaut about Vigo, eliciting from the director a wealth of brilliant ideas. A technical documentary on L'Atalante by Bernard Eisenschitz goes into amazing detail on the editorial crimes perpetrated on the film, illustrated with clips from the altered 1934 release. Many daily outtakes show the dedicated cast shivering during stage waits before the word action is called.

An animated tribute to Vigo by director Michel Gondry seems out of place, but four insert booklet essays by Michael Almereyda, Robert Polito, B. Kite and Luc Sante all reward careful study.

For more information about The Complete Jean Vigo, visit The Criterion Collection. To order The Complete Jean Vigo, go to TCM Shopping.

by Glenn Erickson

The Complete Jean Vigo - THE COMPLETE JEAN VIGO - A Tribute to a Pivotal Film Artist from The Criterion Collection

Quotes

Trivia

Miscellaneous Notes

Re-released in United States October 19, 1990

Re-released in United States January 16, 1991

Re-released in United States April 5, 1991

Re-released in United States June 16, 2000

Released in United States on Video December 2, 1992

Released in United States 1990

Released in United States May 13, 1990

Released in United States August 1990

Released in United States September 1990

Released in United States September 22, 1990

Released in United States June 28, 1994

Shown at Cannes Film Festival (restored version) May 13, 1990.

Shown at Locarno Film Festival August 2-12, 1990.

Shown at Toronto Festival of Festivals September 6-15, 1990.

Shown at New York Film Festival September 22, 1990.

2000 re-release is a new 35mm print.

Film was restored before its re-release in 1990.

Re-released in Brussels November 14, 1990.

Re-released in Stockholm April 26, 1991.

Re-released in Tokyo November 16, 1991.

Re-released in Paris May 16, 1990.

Re-released in London July 20, 1990.

Re-released in Sydney April 25, 1991.

Re-released in Rome July 1991.

Re-released in United States October 19, 1990 (New York City)

Re-released in United States January 16, 1991 (Los Angeles)

Re-released in United States April 5, 1991 (Chicago)

Re-released in United States June 16, 2000 (Film Forum; New York City)

Released in United States on Video December 2, 1992

Released in United States 1990 (Shown at Telluride Film Festival August 31-September 3, 1990.)

Released in United States May 13, 1990 (Shown at Cannes Film Festival (restored version) May 13, 1990.)

Released in United States June 28, 1994 (Shown in New York City (Films Charas) June 28, 1994.)

Released in United States September 1990 (Shown at Toronto Festival of Festivals September 6-15, 1990.)

Released in United States September 22, 1990 (Shown at New York Film Festival September 22, 1990.)

Released in United States August 1990 (Shown at Locarno Film Festival August 2-12, 1990.)