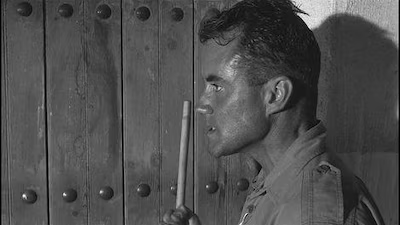

Although Connery had already tried to balance his success as James Bond with more diverse roles like the cocksure executive turned amateur psychologist in Alfred Hitchcock's Marnie and the scheming murderer of Woman of Straw (both 1964), The Hill was easily his most ambitious dramatic role to date. Set in a North African detention camp for court-martialed British soldiers, Lumet's film was based on Ray Rigby's autobiographical play about his own experiences of imprisonment during World War II. Connery was cast as Warrant Officer Joe Roberts, a rebellious prisoner who had previously refused to order his men into a suicide attack and was now being severely disciplined by the sadistic camp sergeant (Harry Andrews). In addition to daily verbal abuse, the main punishment consists of being forced to repeatedly climb a man-made mount of sand and rock under the boiling sun while toting a full backpack.

The grueling physical conditions displayed on the screen in The Hill were just as taxing off screen to the cast and crew but Connery enjoyed every minute of the shoot which included five weeks on location in Almeria, Spain, and two weeks for interiors at the Metro Studios in Borehamwood. For the Almeria set, located in a sandy wasteland called Gabo de Gata, the punishment hill was constructed, utilizing 10,000 feet of imported tubular steel and more than 60 tons of stone and timber. The temperatures rarely fell below 115 degrees and despite the 2,000 gallons of pure water that were shipped in for the crew, almost everyone succumbed to dysentery during the shoot. In Michael Feeney Callan's biography, Sean Connery, cast member Ian Bannen recalled: "We were in the bloody desert and the water and food were ghastly. It'd be hard to find words to describe the location. Tough, that's all I can say. Real tough....Sean was fine at the start - despite the fact the location was as smelly as Aberdeen on a hot day. Fishy, that's what it was like, fish-smelling. Awful."

Upon completion, The Hill was submitted as the official British selection at the Cannes Film Festival and won the Best Screenplay Prize (which it shared with Pierre Schoendoerffer's The 317 Platoon). It also earned Connery the best reviews of his film career to date but its commercial prospects were another story; audiences simply didn't want to subject themselves to an intense, black and white prison melodrama. They preferred Connery as James Bond and so did the entertainment press whose sole interest in The Hill was the fact that Connery had cast aside his sleek OO7 appearance - he didn't wear a toupee or crop his bushy eyebrows. Still, Connery considered The Hill a personal success, and it brought him some intriguing film offers, leading to such offbeat roles as the bohemian poet in A Fine Madness (1966) and the miner turned political activist who formed The Molly Maguires (1970).

Producer: Raymond Anzarut (associate), Kenneth Hyman

Director: Sidney Lumet

Screenplay: Ray Rigby (play), R.S. Allen

Art Direction: Herbert Smith

Cinematography: Oswald Morris

Film Editing: Thelma Connell

Original Music: Art Noel, Don Pelosi

Principal Cast: Sean Connery (Trooper Joe Roberts), Harry Andrews (Regimental Sergeant Major Bert Wilson), Ian Bannen (Sergeant Charlie Harris), Alfred Lynch (George Stevens), Ossie Davis (Jacko King), Roy Kinnear (Monty Bartlett), Jack Watson (Jock McGrath), Ian Hendry (Staff Sergeant Williams), Michael Redgrave (Medical Officer), Norman Bird (Commandant).

BW-124m. Letterboxed. Closed captioning.

by Jeff Stafford